-

Posts

21592 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Profile Information

-

Member Title

MVPMods.com Historian

Recent Profile Visitors

79102 profile views

Yankee4Life's Achievements

Legend (10/10)

-

8 out of 10, 81 seconds. Very unhappy with this score! What a month so far.

-

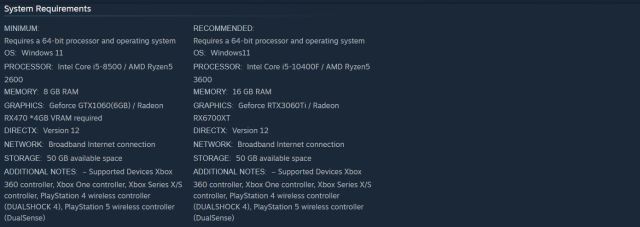

I was going to try to get the demo for this. Forget it. It is a good thing I read what it wanted because I do not have Windows 11. Check it out from the Steam page.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Yo know, I thought I did pretty good with my time today and then I saw that Jim had 33 seconds, which, of course, was very slow for him on a Friday. 🙂

-

4 out of 10, 74 seconds. Well, I'm confident no one will beat that today. 😃

-

Harsh words? Maybe. Also, true. This retirement of the numbers in recent years has really like you said watered down the entire thing. Here is a list strictly from me and me alone that I believe were all players who were very good but at the same time not Monument worthy. And I can hear KC now. Don't worry man, I am getting to your post. Reggie Jackson: Yeah, yeah. World Series hero. But he only was a Yankee for five years. Not enough time to get your number retired. Billy Martin: Marginal player, 1953 World Series hero. Was an embarrassment as a manager due to his antics. Jorge Posada: Now look, I am going to be questioned on this due to the fact that I was and never will be a Posada fan but this guy does not belong in Monument Park with those other catchers there due to his career statistics. I did not grow up with any of these guys but like you heard and read about them. and they are exactly what you said, Monument Park mythology. I agree. The standard just extended over to Sabathia. I kind of feel the Yankees had to get someone because they already grabbed all of the dynasty member players. There was no one else to get. And since that time Sabathia was the only worthwhile one.

-

7 out of 10, 108 seconds. Ok, what the hell?? This time is embarrassing.

-

5 out of 10, 78 seconds. Hey, I'm satisfied with five right.

-

Yankees retiring CC Sabathia’s number shows the sad state of our standard for greatness By Phil Mushnick, New York Post CC Sabathia will be inducted into the Hall of Fame this summer. If we listen closely, we can hear the grandfather, a lifelong Yankees fan, speaking to his grandson: “Oh, yeah, so many memorable moments. Did I ever tell you that I was in Yankee Stadium the day they retired CC Sabathia’s number? Yeah, what a special moment! “What was his number? Darned if I remember. It was one of those big ones, fifty-something. Or was that the number he wore during his eight years with Cleveland?” Everything about Yankee Stadium — except ticket prices, parking fees, and the cost of eats and drinks — seems to be done on the cheap and the cheesy. Last week we learned that the team will hold a pregame ceremony Sept. 26 during which Sabathia’s No. 52 will be retired along with the all-time greats. Was Sabathia an all-time great Yankee? No. He was an all-time pretty good pitcher whose ERA four times exceeded 4.70. He was further known as a slob who spoke vulgarities as a matter of discourse while growing too heavy to field his position. He even grew demonstrably angry with batters for having the audacity to reach first base against him by bunting toward first, as if his corpulence hadn’t begged opponents to take advantage of it. But, you know how it goes … “the game has changed.” One is left with the sense that the Yanks, eager to fabricate a ticket-pushing “special game,” landed on Sabathia’s name and availability. Thus he’ll be honored right up there with Ruth, Mantle, DiMaggio, Ford, Berra, Howard, Rivera, Jeter, Dickey and Gehrig. CC Sabathia tips his cap to the fans in 2019. And good enough has become the new great. Besides, what does it now take to be enshrined in sports halls of fame? Bud Selig, despite playing blind and stupid to MLB’s records-smashing Steroids Era, was a fast-lane entrant to the Baseball Hall Of Fame. The Basketball Hall of Fame is swollen with college coaches whose fame and financial fortunes were predicated upon documented and sanctioned cheating. Finally, Joe Biden bestowed the country’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Honor, on Megan Rapinoe — for many Americans the most repulsive, proudly unsportsmanlike, self-smitten, self-entitled, and anti-American athlete ever to compete on an international stage.

-

9 out of 10, 90 seconds. I don't care if I got nine right because these were some tough questions.

-

This month is going to be tough on me because I am facing five Tuesdays in March. I know we all have to but Tuesday is the worst for me. At least all of you do pretty well and since I don't know what India did in the World cup in any year or any other question that pertains to that &^%$ sport of soccer, I am beat. 😭

-

10 out of 10, 44 seconds. With questions like the ones I had (who was known as the Bambino?) I had to get them all right but the time?? Ok, here are the final results from last month. It was a close one.

-

7 out of 10, 76 seconds. I thought I did better than this but I was tripped up on a Nolan Ryan question and two others.

-

You said you were looking for a copy of 2K12. This is the 2011 version and that is a HUGE difference from the 2012 one. 2K11 is much cheaper and easier to acquire.

-

Yes. I am sure when you get the copy of 2k12 in your hands it will have the provided serial number there. When you have that you'll be off to the races.

.thumb.png.aad86864e15cfc69f40c1da76dccd975.png)