-

Posts

21574 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

10 out of 10, 44 seconds. These questions thankfully were on baseball history and not on baseball card questions, which I know very little about. For example one I got was 'who was the winning pitcher in game seven of the 1955 World Series?" The answer of course is Johnny Podres.

-

5 out of 10, 73 seconds. Another Tuesday. That explains it all. I got the same question and I got it right. I guessed it.

-

9 out of 10, 82 seconds. Good score but I was too slow for my own good.

-

Oh good Lord. I pay attention to Scranton and Trenton as much as I do the Yankees. I got to find out about these guys now.

-

What league are the Savannah Bananas in?

-

9 out of 10, 39 seconds. I missed one I shouldn't have and then have you ever had a day when you thought you went pretty fast and then discovered that you had a slow day? That's what I had today. One week left. This is going to be a close one.

-

9 out of 10, 60 seconds. Some tough one today that had to read over but it was ok just not time-wise.

-

As they say in baseball you were in the zone! Great job.

-

Yeah, that wasn't too long ago either.

-

It could be. He's known for that but 32 seconds is tough to beat no matter how you look at it.

-

Good going man! 32 seconds is going to be tough to beat.

-

10 out of 10, 38 seconds. This leaves the door wide open for everyone to run right past me. Stop and wave if you have time! 🙂

-

5 out of 10, 60 seconds. Again a bad day. This has been a forgettable week.

-

6 out of 10, 102 questions. From question one to nine I struggled. Number ten was thrown at me because it was so easy (In 1977 what game number was it where Reggie Jackson hit his three home runs?)

-

Voicebox: Open-Source AI Generated Kuiper & Krukow Audio for MVP 2005

Yankee4Life replied to HFLR's topic in Mod Research

I don't know what to say. This is beautiful!! I am especially impressed with how Kuiper said Yoshinobu Namamoto as if his name was part of the original out-of-the-box assortment of players that were said by Kuiper and Krukow. Thank you Hector and thank you to Omardj38 for showing you this. I got a feeling this is really going to take off. -

7 out of 10, 42 seconds. I don't get it either but i did well today but that is in part of some very easy (four of them) baseball questions.

-

3 out of 10, 81 seconds. Not good at all and with the tough days coming.

-

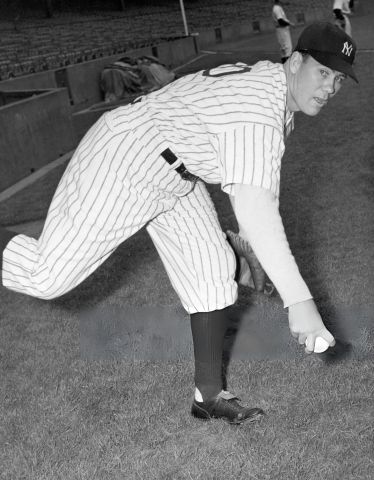

Tiny Bonham This next player is a pitcher who played his entire career in the 1940’s so it is understandable that the casual fan to have never heard of him but if you have played any of the Total Classics 1940’s seasons you would have seen him there. Bonham would not see the next decade but that’s part of his story. Read on. Pitcher Ernie Bonham was known as “Tiny” — though he was anything but — and was one of the few masters of the forkball, the slower ancestor of the split-fingered fastball. Ernest Edward Bonham was born on August 16, 1913, in Ione, California. He called his hometown “one of those ghost towns from the gold rush days.” His grandfather was a 49er; he had come from Missouri to join the 1849 gold rush. Ernie was the 13th of 14 children of Andrew and Clara Bonham. Tiny Bonham got his ironic nickname because he stood 6’2″ and weighed well over 200 pounds with “a torso like a blacksmith,” according to Sporting News publisher J.G. Taylor Spink. Many stories referred to his large size, but none suggested that he was fat. He said his size and strength were the product of “manual labor of the toughest kind.” He grew up doing chores on the family farm and worked on the Oakland docks and in a northern California lumber camp. Some literal-minded writers tried to change his nickname to “Jumbo,” but it was “Tiny” that stuck. He told a radio interviewer, “Call me Ernie, call me Tiny, call me Jumbo, call me anything, just as long as I can go on winning.” He preferred football in high school, but was steered to professional baseball by a fireman he met while pitching for a lumber company team: George Oeschger, the brother of Joe Oeschger, who had pitched a 26-inning game for the Boston Braves in 1920. Oeschger recommended him to Yankee scout Joe Devine, who signed him to a contract with Oakland in the Pacific Coast League in 1935. Bonham rose through the Yankee farm system by way of Modesto, Akron and Binghamton. With Oakland in 1937, he pitched a seven-inning no-hitter against Seattle. At Kansas City the next year, he suffered the first bout of back pain that would limit him throughout his career. He traced the problem to an injury in his lumber-camp days. The 1940 Yankees were coming off an unprecedented four straight World Series championships, but they were stuck around the .500 mark in August. Manager Joe McCarthy asked his longtime friend, Kansas City manager Billy Meyer, to recommend pitching help, and Meyer sent Bonham to New York. When Bonham arrived in early August, shortly before his 27th birthday, the Yankees had fallen nine games behind the league-leading Detroit Tigers. He won five of his first seven decisions, and then on September 19 defeated Cleveland’s ace, Bob Feller, to boost the Yankees into first place for a few hours. That was their high tide; they finished third, two games behind the Tigers. McCarthy said the Yankees would have won the pennant if they had had Bonham for the full season. The rookie righthander contributed a 9-3 record and a 1.90 ERA. It was computed as 1.91 at the time, because fractions of innings were rounded off; Bonham pitched 99 1/3 innings. Either way, it was by far the lowest in the American League for pitchers with at least 10 complete games (Bonham had exactly 10), and that was generally understood to be the qualification for the ERA championship. It is unclear whether there was a rule to that effect, but the practice was clear: As late as 1990, Macmillan’s official Baseball Encyclopedia (Eighth Edition) did not recognize Yankee pitcher Wilcy Moore as the 1927 ERA leader because Moore, primarily a reliever, pitched only six complete games despite working 213 innings. Whatever the rule or the accepted practice, the league recognized Feller as the ERA leader at 2.62 (later recalculated to be 2.61) in 320 1/3 innings. The Sporting News finessed the issue by anointing Feller as the leader “for hurlers in more than 100 innings,” conveniently leaving Bonham out. (Since 1950, rule 10.22(b) requires a pitcher to work one inning for each scheduled game to qualify for the championship.) Bonham threw a high, hard fastball, but he said his best pitch was the forkball: “It sinks and is a fine change of pace.” The forkball, thrown by wedging the baseball between the index and middle fingers, took a sudden dive as it approached the plate. Few pitchers used it, perhaps because it requires a large hand and long fingers to throw it comfortably. Bonham said he learned it from a failed Yankee prospect, Frank Makosky, at Kansas City in 1938. He was also known for outstanding control. Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich commented, “When he walked as many as two men he was having a bad day.” Bonham walked 1.67 batters per nine innings during his career. He worked out with a three-pound iron ball about the size of a baseball, swinging and squeezing it before and during his starts. He said an Oakland coach and former pitcher, Wee Willie Ludolph, had explained that handling the heavy ball had the same effect as a hitter swinging two bats before he went to the plate: It made the baseball feel lighter. (Mariano Rivera, the ace reliever of the Yankees, used the same device 60 years later.) Before the 1941 season the Yankees sent Bonham to Johns Hopkins University for a diagnosis of his back pain. Doctors told him to sleep on a board and fitted him with a “whalebone corset” to support his spine. The pain would not go away. He missed six weeks in 1941 and was able to start only 14 games, with a 9-6 record and an excellent 2.98 ERA. McCarthy frequently gave him extended rest between starts. The 1941 Yankees reclaimed their accustomed spot atop the American League standings. Bonham was McCarthy’s choice to start the fifth game of the World Series against the Dodgers; his 3-1 victory gave the Yankees the championship. Joe DiMaggio caught a fly ball for the last out and handed the ball to Bonham. During the raucous clubhouse celebration, the normally reserved McCarthy climbed on big Tiny’s back (ouch) and rode him around the room. Speaking to reporters after the game, Bonham deadpanned, “It was the worst day of my career, I guess, because I struck out four times and that’s not right for a slugger like me.” He was known for his cheerful personality and ready wit. Years later, after his Pittsburgh teammate Ralph Kiner sent a home run soaring over the tall scoreboard at Braves Field in Boston, Tiny shouted to the Braves’ pitcher, “Tell your outfielders to play higher.” There was no talk of back trouble in 1942. Bonham dominated with a 21-5 record and a 2.27 ERA, second best in the league. He led with six shutouts and tied for the lead with 22 complete games. He allowed less than one walk per nine innings and struck out nearly three times as many batters as he walked, the best ratio in the majors. Baseball writers ranked him fifth in the Most Valuable Player voting; his teammate, second baseman Joe Gordon, won the award. The Yankees won 103 games and faced no significant challenge. Bonham’s twentieth win clinched the pennant on September 14. But the St. Louis Cardinals beat them four games to one in the Series. Bonham lost the second game, 4-3. In 1943 he won 15 for the Yankees’ third straight pennant-winner; McCarthy’s club had raised seven flags in eight years. Bonham’s 2.27 ERA was again second best in the league. This time the Yankees turned the tables on the Cardinals, winning the Series in five games. Bonham was again the loser in Game Two, giving up two home runs while striking out nine in eight innings. The Cardinals won, 4-3, behind the brother battery of Mort and Walker Cooper, whose father had died a few hours earlier. During the off-season, draft-board doctors studied x-rays of Bonham’s back and classified him 4-F — physically unfit — so he returned for 1944, when most of his teammates had gone to military service. He compiled a 12-9 record with a 2.99 ERA, but the Yankees’ makeshift lineup dropped to third place as the St. Louis Browns won the only pennant in their history. In 1945, battling several flare-ups of back trouble, he lost more games than he won for the first time, finishing 8-11, but his ERA was still better than average. After the Yankees fell to fourth place, their new owner, the unpredictable drunk Larry MacPhail, proposed cutting Bonham’s $18,000 salary in half. They settled somewhere in between. On May 11, 1946, Bonham shut out Boston on two hits to stop the Red Sox’ 15-game winning streak. (Boston won the pennant anyway.) He pitched an odd first inning on August 10 against the Red Sox: He gave up two hits but retired the side on four pitches. Wally Moses singled on his first pitch, and then was thrown out stealing on the first offering to Johnny Pesky. Pesky singled on the next pitch and Dom DiMaggio hit into a double play on Bonham’s fourth pitch of the inning. Given his excellent control, it’s easy to understand why batters came to the plate swinging. Between bouts of back and arm pain, he was able to start only 14 times in 1946, posting a 5-8 record and a 3.70 ERA, the highest of his career so far. Manager McCarthy quit early in the season-driven to drink even more than usual by MacPhail’s meddling, some said-and the Yankees finished third. After the season, MacPhail promised a housecleaning. In one of his first moves, he swapped Bonham to Pittsburgh for minor-league pitcher Art Cuccurullo and, according to some accounts, cash. Before Bonham could be traded to the National League, all other American League teams had to waive any claim on him. The 33-year-old was believed to be washed up. The 1947 Pirates must have been a culture shock for Bonham. McCarthy’s Yankees were required to wear coats and ties on the road; the manager would dump any player who dared to question his old-school ways; and the veteran players policed the clubhouse, enforcing a code of hard-nosed professionalism. The Pirates were a rowdy bunch that adopted as their anthem the song “Cigarettes, Whiskey and Wild, Wild Women.” They were also losers. Pittsburgh escaped last place only because Bonham shut out Cincinnati in the season’s final game to lift the club into a seventh-place tie with the Phillies. He won 11 games and lost eight. His old minor-league manager Billy Meyer took over the Pirates in 1948 and moved them up to fourth place, but Bonham was not much help, posting a 6-10 record and 4.31 ERA. He told teammates he planned to retire to his California farm after the 1949 season. His record was 7-4 after his complete-game win over the Phillies on August 27, but he had been complaining of abdominal pain and told Meyer he felt tired all the time. He entered Pittsburgh Presbyterian Hospital on September 8 for an appendectomy. According to news reports, the surgeons discovered intestinal cancer. Bonham died a week later at age 36. The death certificate listed the cause as “irreversible shock [and] cardiovascular failure.” Bonham had a 103 - 72 record with a 3.06 ERA. He struck out 478 and in 1,551 innings he gave up 287 walks or 1.6654 BB/9 for his career. He led the league in fewest walks per nine innings twice, in 1942 and in 1945, and was third in both 1943 and 1944. He ranks 38th in career BB/9; for comparison, Greg Maddux is 53rd at 1.7952.

-

So in other words you had a bad day? 🙂 I'm thrilled with thirty seconds. I usually don't get that low.

-

10 out of 10, 30 seconds. A great day all around...until Jim gets in here and posts 10 out of 10 with 29 seconds! 😂

-

You killed it today! Good going.

-

4 out of 10, 65 seconds. These were some of the most difficult questions I've had on a Saturday ever.

-

10 out of 10, 36 seconds. Fridays always make up for the last few days. It doesn't matter. If I get them in 30 seconds you'll get them in 29. 😮

-

Thank you Dylan, thank you so much. Now can you please not be a stranger around here?

-

6 out of 10, 49 seconds. There were three of the ten questions that I knew. Four I had no clue on so I wiffed on all of them and I guessed on three and got them all right. So for a Thursday it was outstanding.