-

Posts

27000 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

7 out of 10, 73 seconds. I even got a question from the 1800's right today. Wow.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. A good day but I am not making up any ground. Jim's on a mission and he has an eight point lead. I looked at the calendar and besides the obvious fact that we have exactly two more weeks to go this month ends on a Sunday and that's going to help out Jim immensely because we have easy baseball questions on Friday, difficult ones on Saturday and then it's back to easy on Sunday and with the way everyone gets high scores on those easy days that will help Jim. Unfortunately I have two more weeks of the general questions to deal with and that holds me back.

-

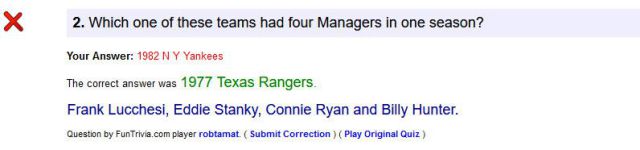

6 out of 10, 64 seconds. Not a good day at all. Checking the ones I got wrong I should have had one of them right. It was this one here. The reason why I said this was because in spring training that year a guy named Lenny Randle beat up Texas manager Frank Lucchesi because Bump Wills (Maury Wills' son) won the starting second base job. He was hurt so bad that I believe he had to be hospitalized.

-

Jim buddy old pal! I got a great idea. Let's call March 1 through the 15th our spring training and our month begins tomorrow. What do you say?? 😬😀 Now everyone while I don't know what Jim actually said I can guess his answer to me can not be repeated out in the forums. 😉

-

Luis Aparicio The name Luis Aparicio is closely linked with Venezuela. Both Luis Aparicio Ortega (Ortega) and his son, Luis Aparicio Montiel (Aparicio), had a significant impact on bringing the game of baseball to new heights in Latin America. For that reason, many say that when talking about one, you can’t help but think of the other. The younger Aparicio was much more than an outstanding baseball player whose endurance, defense, and speed during an 18-year old major-league career earned him a spot in baseball’s Hall of Fame. He was a symbol of the growth and development of the game of baseball in Latin America — specifically in Venezuela and in his hometown of Maracaibo. Aparicio’s place among the greatest players in baseball signified the climax of a cycle of progress for the game of baseball, which has become the national sport of Venezuela and an intrinsic part of its cultural heritage. To fully understand the significance, impact, and legacy of Aparicio’s career, one needs to take a journey back into the first steps of the game in Maracaibo. The emergence of baseball in Maracaibo began around the turn of the 20th century when an American businessman, William Phelps (who later became a media mogul and philanthropist), opened the first department store in town, the American Bazaar. While he imported baseball equipment from the United States, he also saw the need for educating local children about the game in order to sell his merchandise. Phelps became a baseball enthusiast and taught schoolkids the rules of the game, which they quickly understood. He served as the first umpire of documented games and built the first baseball field in the coastal city of Maracaibo. Through the years, the region had a constant flow of American workers from oil companies who helped shape the identity of the city as well as the influence of American culture. Baseball was no exception. By 1926, a heated rivalry between Vuelvan Caras and Santa Marta was catching the attention of followers and local sports media. In fact, the first big hero of local professional baseball was a shortstop from Vuelvan Caras, Rafael “Anguito” Oliver. Early on, the media shone a spotlight on the role of the shortstop. Oliver became an icon and two brothers were some of his biggest fans — Luis and Ernesto Aparicio Ortega. The Aparicio Ortega brothers (in the Latin American custom, they used their father’s and mother’s surname) were also natural athletes; Luis enjoyed soccer but ended up practicing baseball with Ernesto. Both became quality infielders. Luis, however, became the big star, the super athlete, while Ernesto, who had great playing tools, concentrated on learning the game as a science. He became a successful manager, coach, and team owner, transmitting his knowledge over generations. Luis gained fame for his great plays and intelligence in the position of shortstop. He became a reference, a master, and a key player sought by many teams throughout the country. He played in both professional leagues in the country, in Caracas and Maracaibo. He became the first player “exported” from Venezuela when he signed with Tigres del Licey of the Dominican Republic in 1934. Also in 1934, Ortega and his homemaker wife, Herminia Montiel, welcomed their son Luis Ernesto Aparicio Montiel. By the time Aparicio was born in Maracaibo on April 29, his father was shining as one of the first baseball superstars of Venezuela and Latin America. Ortega was an All-Star player and one the most famous players ever of Venezuelan baseball. “An artist in the shortstop position,” many called him. Baseball was his life. Aparicio recalls his mother washing baseball uniforms for his team and talking about baseball all day. From the age of 12, when he played shortstop for a team called La Deportiva, Aparicio displayed the grace and elegance he learned from his father. From then on, Aparicio was a member of several teams in Maracaibo, Caracas, and Barquisimeto. He was constantly moving with his family, depending on the time of year and which team his father was playing for. That was his life: baseball, the stardom of his father, the knowledge of his uncle and whatever the game brought to the family table. In 1953, Caracas hosted the Baseball Amateur World Series, and Luis Aparicio, then 19 years old, was selected to represent Venezuela. It was his first big tournament, and he played shortstop, third base, and left field. Although Cuba won the tournament, Aparicio was recognized both in the stands and in newspapers as the most electrifying player, who made great plays and showed security and maturity in all positions. Fans waved white handkerchiefs during this tournament, praising the teenager with great speed and a solid glove. All eyes were on him for the first time, but the name of his famous father would always be on his shoulders if he chose to be a professional player. Soon after the Amateur World Series, the day arrived. Aparicio had to tell his parents he was quitting school to become a professional baseball player. His mother was not happy with the decision. His father, on the other hand, told him something that would stand out in his mind for the rest of his career. “Son, if you are going to play baseball for a living, you will have to be the number one always,” said his father. “You will never be a number two of anybody, always be the number one.” That winter, the best four teams in Venezuela played in the country’s first national tournament. The teams — Gavilanes and Pastora from Maracaibo, and Caracas and Magallanes from Caracas — rotated their games in four cities and it was the first tournament played under the umbrella of major-league baseball. Aparicio signed with Gavilanes and his debut was scheduled for November 17, 1953, in Maracaibo. That day it rained, and his debut was postponed until the next day, November 18, which is a special holiday in Maracaibo. The city celebrates the day of its lady patron, the Virgin of Chiquinquirá, and festivities are held all around. Among them is the special baseball game between the crosstown rivals Pastora and Gavilanes. Aparicio’s father, Ortega, who also played for Gavilanes, led off the game against Pastora’s Howie Fox, a major-league veteran. After the first pitch, Ortega went back to the dugout and pointed to his son with his bat, signaling it was time for Luis to take his father’s bat and replace him at home plate for his first official at-bat. The crowd of 7,000 gave a 15-minute standing ovation to this simple but magical gesture. They were recognizing Ortega — known as “The Great of Maracaibo” — for his outstanding career, his talent as the best shortstop in Venezuelan baseball, for his dedication on the field, and for more than 20 years of contributing to the development of the game in Maracaibo. At the same time, people were showing Luis the huge burden he had on his shoulders for carrying his father’s name, and for the responsibility he had on the field from that moment. Aparicio ended up being named the best shortstop of the tournament. By December, the Cleveland Indians were negotiating with him. Gavilanes manager Red Kress, who was a coach for the Indians, spoke with general manager Hank Greenberg about signing Aparicio, but Greenberg replied that he thought Luis too small to play baseball. Chico Carrasquel, who was playing for Caracas and Chicago at the time, talked to Chicago White Sox general manager Frank Lane and told him about Luis, asking him to sign the youngster before someone else did. Caracas’s manager, Luman Harris, also talked to Lane. Soon after, Lane sent an offer and a contract for Aparicio with a $10,000 check. Young Luis became a member of the White Sox. In October 1955, the White Sox traded Chico Carrasquel to the Cleveland Indians, leaving the door open for Aparicio. When Lane announced the trade, a Chicago journalist said: “You are trading your All-Star shortstop? You will need a machine to replace Chico.” Lane replied, “Yes, that’s precisely what we have — a machine, and his name is Luis Aparicio.” Aparicio was named the American League Rookie of the Year in 1956. He was the first Latin American player to win the award. He finished with a .266 batting average and a league-leading 21 stolen bases, and also led the league in sacrifice hits. The stolen base as a strategy was becoming less and less used in baseball in those years. Aparicio revived the essence of the stolen base from the moment he reached the majors. He injected the White Sox with the game of speed, the Caribbean game, where speed is a key. He was praised for his defense but during his first season had 35 errors. Luis needed work on his throw. Venezuelan journalist Juan Vené, who covered Aparicio’s entire career, recalled, “Fans were afraid to sit behind first base and they were really aware of the throw every time Aparicio was fielding a grounder because the ball often ended into the stands.” In 1958, Aparicio won his first Gold Glove, was named to his first All-Star Game, hit .266, and led the league in stolen bases for the third consecutive year, with 29. Chicago ended up in second place for the second year in a row behind the Yankees. The situation in the American League was tough. The Chicago White Sox was an outstanding club but the Yankees were the Yankees, and in those years they simply dominated baseball. There were no playoffs. To go to the World Series they just needed to finish first in the American League. The White Sox needed to reach one more step, and they did it in 1959. That season, the White Sox won 94 games and finally won the pennant. Among the keys to their success were Aparicio’s base-stealing skills and his defense along with his double play partner and close friend, Nellie Fox. Aparicio ended up second to his double-play partner Fox in the voting for the American League’s Most Valuable Player. He stole a career-high 56 bases that year. He realized no one in baseball was better than him at stealing. His speed was a key to victory. He led the team in runs with 98. After their great season, the White Sox lost the World Series to the Dodgers in six games. Aparicio hit .308 (8-for-26), and although he was thrilled to participate in the fall classic, he was deeply frustrated in not winning the Series. “ Hoping to return to the World Series in 1960, the White Sox instead slipped to third place. They fell to fourth place in 1961 and fifth in 1962. The Sox wanted to rebuild their team, and in January of 1963, Aparicio and veteran outfielder Al Smith were traded to the Baltimore Orioles for Ron Hansen, Pete Ward, Dave Nicholson, and Hoyt Wilhelm. The trade was a jolt to Luis, but he was moving to a contending team built around a foundation of power and pitching. Aparicio added speed to the Baltimore lineup, winning two more stolen base titles in 1963-64 to give him nine consecutive seasons as the American League stolen base champion, an all-time record. More importantly, he helped solidify the Oriole defense. Luis and future Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson formed one of the best shortstop-third base combinations of all time. In 1966, the Orioles won the American League pennant, and Aparicio once again faced the Dodgers in the World Series. Although his offense was not as solid as it was in 1959, he still contributed with four hits and great defense during the series, which the Orioles swept in four games. It was first and only championship ring of his career. He came back to Maracaibo as a hero, dedicating his part of the title to his parents, who were his biggest supporters. In November of 1967, Luis was traded back to the White Sox. As a veteran player, he became the team leader and mentor. During his second stint in Chicago, his glove was still his great tool, though his speed was not the same. He worked on his offense and in 1970, at the age of 36, batted a career-high .313. Before the 1971 season, Aparicio was traded to the Boston Red Sox and played with them for three more seasons. In two of them was he was selected to the All-Star Game. In 1973, at the age of 39, he batted .271 in 132 games and stole 13 bases in 14 attempts. On March 26, 1974 Aparicio was in the Red Sox spring camp when he got the notice that he was being released. He wanted to play one more season; he was 40 and still felt he had it. When he went back to the hotel he had a letter from Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. It was an open contract that had a note saying: “You put in the amount to play for the New York Yankees.” Aparicio sent the envelope back with a note that said: “Dear Mr. Steinbrenner, thank you very much for your offer but I just get released once in my lifetime.” That was the end of Aparicio’s playing career. He went back to Maracaibo that day with his family. From 1956 to 1973, no other shortstop was more dominant in his position than Luis Aparicio, who won nine Gold Gloves. He was a profound influence on the game during his era with his speed, helping to revive the stolen base as an offensive weapon. He was selected to 10 All-Star teams. He played in two World Series and won one, and he set the most significant personal record for himself: No player had played more games at his beloved position in the major leagues than he (2,583). (The record has since been broken by Omar Vizquel.) He finished his career with 2,677 hits, a .262 batting average and 506 stolen bases. After 10 years of eligibility and a huge crusade by many Hispanic journalists pushing his candidacy for the Hall of Fame, he was elected to the Hall in 1984, becoming the first Venezuelan to ever receive this form of baseball immortality. “This is a triumph of Venezuela for all Venezuelans,” said Aparicio when he heard of his election. After his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Aparicio’s status of celebrity increased greatly. He became known as the most important and influential Venezuelan athlete of all time, the most revered and followed. He also made several trips a year to the US to participate in autograph sessions, fan festivals and former player activities. He was a constant supporter of Hall of Fame gatherings, including All-Star games and Cooperstown induction weekends. Aparicio has since become an active baseball follower and his voice is present through his social media accounts, where he has provided opinions and personals perspective of issues around baseball. Most notably in 2017 he was invited to participate in a ceremony honoring the Latino members of the Baseball Hall of Fame prior to the 2017 All-Star Game in Miami, Florida. Aparicio respectfully declined the invitation and publicly stated: “Thank you for the honor @mlb, but I cannot celebrate while the young people of my country are dying while fighting for freedom” Maracaibo still remembers every November 18 as part of the festivities around the Virgin holiday, the anniversary of Luis Aparicio’s debut. At the Aguilas del Zulia game, Aparicio has made the ceremonial first pitch. Every year the Luis Aparicio Award is given to the best Venezuelan player of the major-league baseball season. It was a tribute to his career and to the memory of his father. Much more than a great player, Aparicio was recognized as a great human being. Most people knew Luis for his playing feats, but ignored his great heart and family values. During his career the integrity he brought to the game was one of his strongest assets. He gave everything he had to win and help his teams. He played simultaneously for 19 years in Venezuelan baseball, doubling the amount of work year round. As a major-league player he played fewer than 130 games in a season only once. Maybe his greater value was how he embraced and understood his position and his significance on and off the field for the people of Venezuela, a country filled with social problems that universally celebrates the achievements of its people. He was much more than an icon. People always expected the best from him, and he gave nothing but the best both as a player and as a human being, working hard enough and using his abilities to be among the greatest players of all time. He had huge shoes to fill under the shadow of his father and he never let this issue pressure him during his life. Luis Aparicio assumed a social responsibility and went beyond expectations.

-

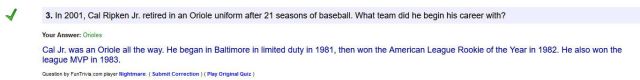

9 out of 10, 36 seconds. I missed one that I misread and if i had not done that I'd of had ten. Frustrating month. I am eight point behind Jim with over two weeks to go. He's having a great month.

-

4 out of 10, 119 seconds. Hey, I got four so that's something. Jim has a seven point lead on me and the way I am playing it's going to be tough.

-

Yes. They are a major disappointment.

-

Gerrit Cole to miss at least 1 to 2 months as Yankees ace visits noted surgeon The Yankees will be without Gerrit Cole to at least the start of the season. Yankees ace Gerrit Cole will be out at least one-to-two months and will head to Los Angeles for an appointment with noted sports surgeon Dr. Neal ElAttrache, The Post has learned. Several Yankees doctors and ElAttrache have viewed Cole’s preliminary film, and while none has detected a tear in his ulnar collateral ligament, there’s enough concern about the ligament that ElAttrache has suggested an in-person visit. Word is that the defending AL Cy Young Award winner will be out for an “extended period,” although for now, the hope and belief is that Cole has a chance to return sometime in May or early June. The initial readings of Cole earlier in the week were optimistic, with the belief the issue could be resolved with rest and other conservative treatments, but ElAttrache has recommended more testing, raising the level of worry. Yankees manager Aaron Boone publicly ruled out Opening Day, but it’s clear Cole will need more time than that now. At the very least, Cole will need to wait for swelling and inflammation to subside, and once that does, he would need to re-ramp back up to get into major league pitching shape. The 33-year-old has shown his usual excellent velocity and command this spring, but his recovery, normally no problem for one of baseball’s most dependable starters, has been an issue. His most recent spring outing was a three-inning, 47-pitch live batting practice Thursday. “His recovery, before getting to his next start, has been more akin to what he feels during the season, when he’s making 100 pitches,” Boone said Monday, when Cole underwent the initial MRI exam. That turned out to be just the start of testing that has been going on for a few days and will continue in California with ElAttrache. Former Yankees great Masahiro Tanaka was able to pitch successfully with a weakened elbow ligament, but many pitchers are not. Gerrit Cole talks to the press at the start of Yankees spring training. Since the start of the 2020 season, no one has pitched more innings in baseball than Cole (664), who has performed like the workhorse the Yankees believed he would be when they signed him to a $324 million contract. Cole has been the rare combination of excellent and durable, never undergoing Tommy John surgery and consistently taking the ball for the Yankees every fifth day. There is no good time to lose Cole, but extended missed time this year would be especially devastating. Gerrit Cole will miss at least 1-to-2 months. In what will be an all-in year for the Yankees — who mortgaged part of their pitching future in a trade for Juan Soto, who will be a free agent after this season — there are significant questions behind Cole in the rotation. Marcus Stroman pitched just 24 innings in the second half of last season due to hip and rib-cage issues. There are questions of durability and effectiveness with lefties Carlos Rodon and Nestor Cortes, both coming off seasons to forget. In his first full season as a major league starter last year, Clarke Schmidt was OK (4.64 ERA) but not special.

-

Thanks for the video. I think is a great addition here. And just to be clear this isn't my thread. Yeah I did start it back in 2005 but anyone can come in and contribute. Or, if you want you can request a player.

-

6 out of 10, 79 seconds. Well, better than yesterday at least I can say that. 🤷♂️

-

Chris Chambliss On October 14, 1976, the Kansas City Royals and the New York Yankees were locked in the winner-take-all fifth game of the American League Championship Series at Yankee Stadium, going into the bottom of the ninth inning. The Royals had won Game Four the night before to force the deciding game. This evening, Royals third baseman George Brett had hit a three-run shot in the top of the eighth inning to tie the score at six, and the Royals seemed to be gaining momentum in their first-ever postseason series since joining the American League in 1969. As the bottom of the ninth began, Yankee first baseman Chris Chambliss waited for Royals relief pitcher Mark Littell to finish his warm-up pitches, before stepping into the batter’s box. As Chambliss waited, Yankee public address announcer Bob Sheppard was cautioning the crowd of over 58,000 about throwing debris onto the playing field. The game had already been stopped several times for bottles, firecrackers, beer cans, and rolls of toilet paper being thrown from the stands. Behind Chambliss, Sandy Alomar settled into the on-deck circle, telling batboy Joe D’Ambrosio, “He’s gonna hit it out,” indicating Chambliss. “He’s got to hit one out, because if he doesn’t do it, I’m on deck.” Alomar, a steady defensive infielder, batted .239 that year. “I was a little anxious,” Chambliss said, standing by the bat rack, annoyed by the delay. “It was cold, too. That was a trying little time there.” Littell was annoyed by the delay, too. With an 8-4 record, 16 saves, and a 2.08 ERA, the 23-year-old possessed a live fastball and a wicked slider. The delay prevented Littell from staying loose, and interfered with his rhythm. Finally, at 11:13 PM, Chambliss stepped into the box, and home-plate umpire Art Frantz yelled “Play ball.” Chambliss was 10-for-20 with 7 RBIs in the playoffs. He narrowed his eyes. “I knew Littell was going to throw a fastball,” he said later. Littell nodded at catcher Buck Martinez, and delivered a high inside fastball. Chambliss reared back, stepped into the pitch, and smashed it over the right field wall. Chambliss stood momentarily at home plate watching the flight of the ball carry through the autumn air, not sure if it would go. “Sometimes you’ll see players drop their bats at home plate to admire the ball as it goes out of the park. They know they hit it so well, it’s a home run from the moment it leaves their bats. This wasn’t one of those. The ball I hit was more what you would call a towering drive with a lot of height, but I didn’t know if it had enough distance to make it out. When I hit the ball, it looked as if the Royals right fielder had a bead on it. He moved back as if he was going to catch it. But at the very last second, he backed into the wall and the ball cleared it.” On the bench, Thurman Munson, in his catcher’s gear, leaped onto the field, tracking the ball into the bleachers. Chambliss then half-leaped to first base, unable to break into the home-run trot, as thousands of fans stormed the field, seemingly right at Chris. As he rounded first base and headed to second, the base was ripped from its support by Yankee fans eager for some memorabilia. Chris ran by, touched the base with his right hand, and continued to run through the maze of humanity. Chambliss fell in the base path, accidentally knocking a body over, then he tagged third and headed home. “I gave him a pretty good forearm,” he said later, with a laugh. When fans tried to grab his helmet, Chambliss tucked it under his arm, like a football. Like a fullback looking for a small hole at the line of scrimmage, Chambliss was spun completely around in a circle and powered his way through the throng. He was then escorted to the Yankee clubhouse by two policemen. “Home plate was completely covered with people,” Chambliss said later. “I wasn’t sure if I tagged it or not. I came in the clubhouse and all the players were talking about whether I got it. I wasn’t sure, so I went back out.” Graig Nettles urged Chambliss to return to home plate to make it official. “I wanted to make sure there was no way we were going to lose it,” said Nettles. Dressed in a police raincoat to avoid further harassment from the scores of fans still milling the field, Chambliss jogged out to home plate — found it had been dug up and removed, replaced by a hole — touched the hole before Frantz, and returned to the champagne party. In a most historic and memorable fashion, Chris Chambliss delivered the first American League pennant to New York in the renovated Yankee Stadium, and the first one for the team since 1964, ending a 12-year drought. It was a dramatic victory for the Yankees, won by a player who prided himself on steady professionalism, not drama. Carroll Christopher Chambliss was born December 26, 1948, in Dayton, Ohio. His father was a Navy Chaplain, so his family was frequently on the move, relocating across the country. Chris lived in Xenia, Ohio, St. Louis, Chicago, and finally in Oceanside, California, where Chris attended high school, playing both shortstop and first base on the varsity baseball team. Chambliss had been drafted in 1967 and 1968 by Cincinnati, but declined both times and enrolled at UCLA. In the January 1970 draft, the Cleveland Indians picked Chris with the first pick in the first round and assigned him to their affiliate in Wichita of the American Association, Cleveland’s top farm team. Chris earned Rookie of the Year honors while at Wichita, becoming the first freshman to win the batting title, posting a .342 average. Chris also hit seven home runs and collected 52 RBIs. Because of conflicting military reserve commitments, Chambliss was not called up to the big leagues at the end of the season. During spring training in 1971, the Indians had to make a decision on Chambliss’ future. Veteran Ken Harrelson was the incumbent first baseman, though returning from an injury, and Chambliss suffered a leg injury that was thought to be a pulled right thigh muscle. So the Tribe sent Chris back to Wichita at the start of the 1971 season so that he could get accustomed to playing the outfield. The Cleveland front office believed that Chris would be able to contribute faster by learning a new position, and at the same time keeping both bats in the lineup. He made his his debut on May 28 in Chicago. Pinch-hitting for shortstop and future fellow Yankee teammate Fred Stanley in the eighth inning, Chambliss grounded out. By this time, however, Harrelson was struggling with the Tribe, hitting .209 at the time of Chambliss’ debut. Hawk would only play three more weeks before calling it quits in favor of a short-lived professional golf career, turning first base over to Chris. Chambliss never looked back, hitting safely in 14 of his next 15 games, smacking 114 hits in 111 games in 1971, including 20 doubles, nine home runs, 48 RBIs, and a .275 batting average and was named American League Rookie of the Year by both the Baseball Writers’ Association of America and The Sporting News. The Indians fared better in 1972 and behind Cy Young Award winner Gaylord Perry and a solid foundation of good, young talent, 1973 was shaping up to be quite a team. But third baseman Graig Nettles was dealt to the Yankees in the off-season, and catcher Ray Fosse was traded to Oakland during spring training. On Friday, April 26, 1974, the Indians and Yankees completed a seven-player trade with pitchers Dick Tidrow, Cecil Upshaw, and Chambliss going to New York. In return, Cleveland received four pitchers; Fritz Peterson, Tom Buskey, Steve Kline and Fred Beene. Yankee players offered were less then thrilled at giving up four pitchers. “I can’t believe this trade,” said Yankee center fielder Bobby Murcer. “It means they don’t think we have a winning ball club.” Murcer paid a stiff price for his honesty. He was traded at season’s end to San Francisco. The Yankees finished the 1974 season in second place, two games behind Baltimore, staying in the race until the final series, fans cheering them on to the end. Manager Bill Virdon was named Major League Manager of the Year by The Sporting News. These results were quite different for Chambliss and Tidrow, who had been teammates since their minor league days at Wichita, and were used to the Indians’ losing ways and empty stands. Expectations ran high for the Yankees in 1975 and Chris hit .304 in 1975, as well as fielding at a .991 clip at first base, leading the league’s first basemen in games played (147) and innings (1,299.1), erasing fan doubts about his abilities. The 1976 season would start a string of three straight American League pennants for the Yankees. Billy Martin inserted Chris into the cleanup position in the batting order. Chambliss responded by having his finest year to date, clubbing 17 home runs and 32 doubles, driving in 96 runs, and hitting .293. The World Series ended New York’s season with a loud thud. The Cincinnati Reds swept the physically and emotionally exhausted Yankees in four games, despite Martin’s promise to “get that Red Machine wheel by wheel, axle by axle, if we have to.” In some ways, 1977 and 1978 mirrored themselves for the Yankees. For instance: each year they won the American League East with a slim margin, each year they had a Cy Young Award Winner (Sparky Lyle 1977 and Ron Guidry 1978), each year they bested the Royals in the League Championship Series, and toppled the Dodgers in the World Series both seasons, four games to two. Yet through the incredible turmoil and strife that made the 1977 Yankee season distinctive and memorable, Chambliss was focused and steady. He batted .287, hit 17 home runs, and drove in 90 runs. He also maintained class. The following season was rougher for the Yankees, though: the team suffered more dissension and injuries, with the Yankees falling to 14 games back of the Boston Red Sox. Chambliss continued to be a steady hitter in 1978, batting .274, with 12 home runs, and 90 RBIs. Chambliss won the Gold Glove Award in 1978 with a league-leading fielding percentage of .997, committing only four errors in 1,481 chances. During the 1978 World Series, Chris suffered a broken bone in his right hand, causing him to miss three games in the Series. In spring training, he had a cast placed on his right wrist due to a strained tendon. In spite of stories that the Yankees were pursuing Rod Carew to play first base, Chris had his usual productive year (27 doubles, 18 home runs, .280 batting average and a .994 fielding average). But for the Yankees, 1979 would be a year of not only disappointment on the field, but tragedy and loss off the field as well due to the death of Thurman Munson on August 2nd. During the offseason the Yankees were looking to find a capable catcher to replace Munson. On November 1, Chambliss was traded to Toronto but the Blue Jays already had John Mayberry playing first base, so one month later, on December 6, Chris was dealt with infielder Luis Gomez to the Atlanta Braves. Neither Chambliss nor the rest of the Atlanta team disappointed manager Bobby Cox, or the Brave fans. After a last-place finish in 1979, the Braves finished 1980 in fourth place and a game over the .500 mark. Chambliss again clubbed 18 home runs, while hitting .282 and led the league with 1,626 putouts. In 1982 the Braves topped the Dodgers by one game and the Giants by two games, to give the franchise only their second division title since moving to Atlanta in 1966. Chambliss smacked a career-high 20 home runs and drove in 86 runs for the season. Over the next three years, Chris’ production and playing time decreased. Gerald Perry was a star in the Braves’ minor league system and replaced Chambliss the last month of the 1984 season, a season that saw Chris manage to hit only nine home runs after back-to-back 20-homer years. “I can do everything I’ve been able to do throughout my career, even better,” said Chambliss in 1985 at spring training. “I’d really like the opportunity to play regularly. That’s the way I can be effective.” But Eddie Haas was the new Brave skipper, and management favored the youngster Gerald Perry, seen as a “can’t-miss” prospect. But Perry missed spectacularly, hitting .214 with three homers and 13 RBIs. Chambliss did little better at .235, three home runs and 21 RBIs. Bob Horner took over at first base, with a .267 average, 27 HRs, and 89 RBIs, but the Braves finished fifth with a 66-96 record. Eddie Haas was replaced in late August by coach Bobby Wine. Bob Horner was now getting the most at-bats (483) while playing first base. Chambliss had only 170. In 1986, Chambliss played in 20 games at first base, but led the league with 20 pinch-hits. Chambliss retired with a batting average of .279 and 185 home runs. He is among the career leaders for first baseman in games played (1,962), assists (1,351), putouts (17,771), double plays (1,687) and fielding percentage (.993).

-

3 out of 10, 128 seconds. These questions destroyed me today. I had a Pakistan sports question today. What the hell? Of course I got it wrong!

-

9 out of 10, 85 seconds. I did not know who the 1993 World Series MVP was (Paul Molitor) because I hardly watched that series because the Blue Jays were in it. 😄

-

10 out of 10, 40 seconds. I did not have a good rhythm going so it cost me time. And it was so nice to see everyone playing today. I missed you guys.

-

I am spinning my wheels this month Jim and can not seem to get going.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. I needed this. We all do well on Fridays!

-

2 out of 10, 193 seconds. Where'd this guy go to college, the damned World cup and Nascar. Laroquece and I must have had the same questions. 😀

-

3 out of 10, 142 seconds. Pretty bad day. I've noticed that we kind of get two different baseball difficult questions. First, the difficult ones that you have a shot at and then those who are even more harder than the usual ones. Today they were even more harder than the usual ones.

-

That's usually what I do. 😄

-

4 out of 10, 164 seconds. I got four right which is a big accomplishment in the general questions.

-

7 out of 10, 42 seconds. Ask me baseball card questions and I will give you the wrong answers. 🙂

-

10 out of 10, 52 seconds. No, I don't know what happened. The questions were not challenging. i just didn't get into the right groove today. But you were in a good groove. Fantastic time today and that should win it for today. It's hard to beat that time.

-

6 out of 10, 104 seconds. I had some tough ones that I hope no one else gets like how many home runs did Dave Stapleton have in Pawtucket between 1977 and 1980? The correct answer was thirty which proves you learn something useless every single day.