-

Posts

21604 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

You killed it today! Good going.

-

4 out of 10, 65 seconds. These were some of the most difficult questions I've had on a Saturday ever.

-

10 out of 10, 36 seconds. Fridays always make up for the last few days. It doesn't matter. If I get them in 30 seconds you'll get them in 29. 😮

-

Thank you Dylan, thank you so much. Now can you please not be a stranger around here?

-

6 out of 10, 49 seconds. There were three of the ten questions that I knew. Four I had no clue on so I wiffed on all of them and I guessed on three and got them all right. So for a Thursday it was outstanding.

-

Great and Historical Games of the Past

Yankee4Life replied to Yankee4Life's topic in Baseball History

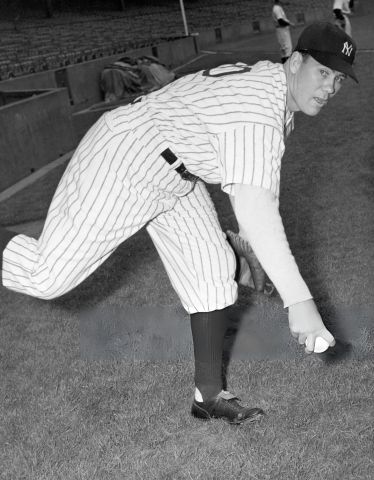

October 6, 1941: Dodgers submit quietly to Tiny Bonham and the Yankees Ernie "Tiny" Bonham, New York Yankees. At the start of Game Three, Brooklyn fans draped a large banner from the railing of the center-field bleachers that read, “We waited 21 years, don’t fail us now.” The sheet proclaimed its message proudly throughout Games Three and Four. But by late in Game Five, the banner was sagging and unreadable, an apt metaphor for the fate of the Dodgers, who wilted in submission to the relentless Yankees machine. Brooklyn and its fans seemed understandably deflated after a crushing defeat in Game Four, when a potential game-winning third strike got away from catcher Mickey Owen and opened the door to a four-run ninth-inning Yankees rally. The fans didn’t hold it against Owen. They gave a him a rousing ovation when he was introduced in Game Five. However, although attendance was a tick higher than it had been for the previous two games, the park was unusually subdued. New York’s stunning comeback had brought mortality into clear focus. The Dodgers went with their best to try to keep the Series alive. Veteran Whitlow Wyatt, the winning pitcher in Game Two, tied for the National League lead with 22 victories that summer. Meanwhile, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy turned to his fifth different starter of the Series, the ironically nicknamed Tiny Bonham, a hulking product of the Oakland, California, shipping docks who approached his assignment with the eagerness of a puppy: “When McCarthy told me I was going to pitch the fifth game I was so thrilled that tears came to my eyes. It was what I had always wanted to do.” New York threatened in the first, putting men at first and second for Joe DiMaggio, but on a 3-and-2 pitch, Wyatt struck out the American League MVP and Owen cut down Red Rolfe at third on the front end of an attempted double steal. Brooklyn mounted a challenge of its own in the bottom half, but after Pete Reiser’s two-out triple, NL home-run champ Dolph Camilli, suffering through a miserable Series, popped harmlessly to short. Charlie Keller began the Yankees’ second with a walk, and Bill Dickey followed with a single up the middle. Reiser had a good chance to catch Keller advancing to third, but his perfect one-hop throw from center skipped through the legs of third baseman Lew Riggs. Wyatt was backing up, which temporarily saved the day, but next came the irrepressible Joe Gordon, who was 6-for-11 in the Series so far with four RBIs. On his second pitch, Wyatt uncorked a wild one that sailed way over Owen’s head and allowed Keller to score the first run. Then Gordon singled to right, driving in Dickey and giving New York a 2-0 lead. The Dodgers showed a fluttering pulse in the bottom of the third. Wyatt, a dangerous hitter, led off with a double high off the left-field wall, advanced to third two batters later when Riggs singled off Bonham’s foot, and then came home on Reiser’s fly out. That perked up the crowd until the fifth, when Tommy Henrich took Wyatt deep, hammering his first pitch over the wall in right, just fair but well gone. “When last seen from the high press box,” Shirley Povich wrote in the Washington Post, “the ball was being pursued by a posse of boys down a street two blocks from the park.” Henrich’s blow put the Yankees up 3-1, and seemed to take the energy out of everyone on the Brooklyn side except for Wyatt. He brushed back the next hitter, DiMaggio, with a couple of fastballs before retiring him on a long fly to center. On his way back to the dugout, DiMaggio had a few words for the Dodgers right-hander. “I didn’t like how a couple of pitches came at my head,” DiMaggio admitted. “When I passed him, I said, ‘The Series is over, kid, so take it easy.’” When Wyatt, the former Sunday school teacher, offered a profane rejoinder, DiMaggio lost his characteristic cool and spun back toward the mound to have it out. Immediately the benches cleared to keep the two men away from each other. No punches were thrown and apparently no feelings were too badly bruised. When DiMaggio returned to his position in center field in the bottom of the fifth, the bleacherites booed lustily and one fan whipped an apple at him, but for Wyatt, it was all in the game. “It’s just one of those things that happens in the heat of battle,” he shrugged. “Joe is a great player and I like him.” The rest of the way was as easy as breathing for Bonham. “You know, it may sound [strange], but I wasn’t as nervous out there as I have been for some league games,” he said. Bonham was known for his forkball, but he claimed he threw it only twice, instead relying almost entirely on fastballs. He wasn’t overly deceptive, but he was extremely effective. He allowed just two baserunners from the fourth inning onward, retiring the side on four pitches in the sixth and three pitches in the seventh. Were it not a World Series game, it would have been a monstrously dull way to spend an afternoon. The Sporting News described the crowd as “still as a morgue.” The only real excitement in the late innings came when a fan in the upper deck in left field carelessly discarded a cigarette and caught a piece of red, white, and blue bunting on fire. With two outs in the ninth, pinch-hitter Jimmy Wasdell lifted a routine fly ball to DiMaggio, an anticlimactic end to a tightly fought World Series. New York took the game, 3-1, and the Series four games to one. The Yankees weren’t new to this. It was their fifth title in six years, but they celebrated as if they had never won before. Indeed, it had been a challenging season – they dropped 16 of their first 31 games and then saw their beloved erstwhile first baseman, Lou Gehrig, die in June. They had earned the right to cut loose. Coach Art Fletcher danced on a trunk in the clubhouse as the team sang its traditional victory song, “The Sidewalks of New York.” McCarthy was late coming in from the field, but when he arrived, his guys belted out another rendition just for him. DiMaggio pushed his way through the madness to hand the baseball to Bonham, who kissed it for the benefit of photographers before giving McCarthy a back ride around the room, with the rest of the team pummeling them every step of the way. As the New York Times described it, “Punches were flying, bodies were swaying, trunks were being banged around, benches were pushed out of place, towels flew through the air. And the noise was terrific.” Brooklyn manager Leo Durocher was ostensibly gracious, ducking into the Yankees’ celebration in his underwear to shake hands with McCarthy and give Bonham a congratulatory slap on the cheek. Back in his own clubhouse, though, he was somewhat less tactful. “[W]e made their pitching look good because we weren’t hitting,” he groused. “No pitcher like that Tiny Bonham today, who was throwing fastballs all afternoon because he does not own a curve, should make us look so bad.” He also sought out home-plate umpire Bill McGowan after the game to remind him of Brooklyn’s displeasure with the veteran arbiter’s strike zone. His players struck a similar tone. Camilli was bellyaching about Brooklyn’s bad luck. “If we’d just got half the breaks, not all of ‘em, the Series right now would be no worse than three games to two in our favor.” Teammate Dixie Walker called the champs “the luckiest club that ever stepped onto a ball field.” McCarthy heard some talk like this from the writers gathered in his clubhouse and was having none of it. “What the hell?” he exploded. “The Dodgers were lucky to win a game. Those Dodgers are a great team. You can’t take that away from them, but don’t expect me to sit here for hours praising them. I have a great bunch of ballplayers of my own.” The degree of the Yankees’ October dominance is nearly incomprehensible. Since 1927, they had appeared in 36 World Series games. They won 32. McCarthy surpassed the Athletics’ Connie Mack and became the first manager to win six World Series titles. Brooklyn was still waiting for its first. Its fans, though, were undeterred. A man named Mike Rinaldi spoke the mantra that would be repeated incessantly in the borough over the next decade and a half, when he told a reporter, “It’s in the bag for next year.” Tommy Henrich's home run in the fifth inning gave the Yankees a 3 - 1 lead. -

8 out of 10, 79 seconds. My luck was so good today that I even got a baseball card question right. I noticed that today's game was not nice to any of our times.

-

7 out of 10, 47 seconds. I am not fooling myself here because I know I was given two baseball questions that really helped me. And the last question I have to thank Mr. Miyagi for. In the 1970s and 1980s, what stimulated increasing interest in karate? Answer: Motion pictures.

-

I've been very fortunate lately. I've also noticed that the hardest baseball questions we get are on Wednesdays.

-

10 out of 10, 51 seconds. 51 seconds? I have no answer for that. But I needed this score since hard days are starting tomorrow.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Not bad today but I have no idea why I hesitated on one of them when I knew the answer.

-

Well I would have to agree. I'm stumped.

-

i was reading over your question and as soon as I saw that you had Windows 11 I saw the problem. That operating system does not work well with Mvp 2005. It is nothing you are doing wrong.

-

Ok Joel Sherman but I reserve the right not to believe anything positive about the Yankees especially this time of year. Ryan Weathers can change Yankees’ 2026 outlook following offseason of continuity by Joel Sherman, New York Post Ryan Weathers is a rare outside acquisition for the Yankees this offseason. For those complaining that the Yankees are running back the same team as 2025, you probably missed that since late July they have added Jake Bird, Angel Chivilli, Yanquiel Fernández and Ryan McMahon. Or four players from a Rockies team that lost 119 games last year. That is a bit of a cheap shot at the Yankees. But also an attempt to note we are not talking about the actual 2025 Rockies running back the majority of a roster. Or, as one general manager who thinks the Yankees did well this offseason said: “They weren’t bad and running it back. They were good and are running it back.” And I am not even sure they are running it back. The Yankees acquired Ryan Weathers, didn’t have an inning of Gerrit Cole last year, and will have a full season of trade deadline acquisitions McMahon, who improved their defense; Jose Caballero, who upgraded their speed/versatility; and David Bednar, who steadied their bullpen; plus Bird and Camilo Doval to perhaps be better for them in 2026. Also, free agents are — key word — “free.” So returning notably Cody Bellinger’s all-around value plus also Trent Grisham’s lefty power, the righty bats of Paul Goldschmidt and Amed Rosario, and the ability of Paul Blackburn and Ryan Yarbough to deepen the pitching staff was not assured. The end result is a team that betting sites generally project to the highest Over/Under win total in the American League entering spring training. Additionally, at this time of year, when I talk to executives I will inquire what their models project win-wise for the New York teams. And I have yet to speak to one that does not have the Yankees at the top of the AL or just off of it. Of course, these are educated forecasts and not certainties — these entities loved the Mets and Braves last year, and hated the Blue Jays. But I like to ask because these are not fans or media but operations trying to filter out bias to fully grasp their competition, and the consensus expects the Yankees to be very good whether you view the Yankees roster as static or not. One GM I thought most thoroughly conveyed a near universal feeling said, “I know it’s not exciting to fans to say we are running it back, but they were good last year. Bellinger is a uniquely good fit for that ballpark [Yankee Stadium]. Their offense was awesome last year, and we have them with the Dodgers to be awesome again this year. “Weathers is a perfect fit because he doesn’t have to give them 150 good innings. If they get 90 from him, that would really help because they may have more pitching coming in June and July [notably Carlos Rodón and Cole], and we like some of their young guys [pitching prospects]. “Winning the offseason is so overrated. If Bellinger played for someone else and they brought him in, that would be viewed as an A-plus move. They got better on the bases and defense as last year went on, [Anthony] Volpe was playing with a busted up shoulder. Cole didn’t play. I look at it and I wouldn’t have done much different from them.” On a technical level, the one player not in the organization last year who could most impact the 2026 team is Weathers, who arrives with these quirky facts: 1. The Padres have had the seventh overall draft pick twice in their 57-year history and took a lefty starter both times — Max Fried in 2012 and Weathers in 2018. Both are now Yankees. 2. His father, David Weathers, once had former major league pitcher, Mel Stottlemyre, as his pitching coach (Yankees). His son, Ryan, had Mel’s son, former major league pitcher, Mel Jr., as a pitching coach (Marlins). 3. The first trade ever between the Yankees and Marlins was July 31, 1996, when David Weathers came to New York for Mark Hutton. The most recent trade between the teams was Ryan for three prospects. Joel Sherman compares the Yankees’ Ryan Weathers trade to that of the Nathan Eovaldi acquisition. Yet, it is another Yankees-Marlins trade that I think of with Weathers. Nathan Eovaldi had begun in the NL West (Dodgers) and was traded to the Marlins. In both places he showed high-end talent, but in part because of injury had not fully refined and was traded to the Yankees after his age-24 season with three years of control left. He came with the reputation as fearless, a hard worker and superb teammate. Eovaldi was good as a Yankee in 2015-16 before missing the entire 2017 season after needing Tommy John surgery. It was not until leaving the Yankees that Eovaldi fully bloomed as a consistent high-quality starter who was way better than that in the postseason and gained a reputation as among the best teammates in the game. Weathers was traded from the NL West (Padres) to the Marlins. In both places he showed high-end talent, but in part because of lost development time in 2020 due to no minor league season (COVID) and injury, he had not fully refined and was traded to the Yankees after his age-25 season with three years of control left and with the reputation as fearless, a hard worker and superb teammate. Weathers’ profile was enticing enough that the Marlins had many offers to try to grab him and see if a new team could keep him healthy, and finish off a trajectory in which in recent years he augmented his high-end fastball with much better spin and a quality changeup. Stottlemyre Jr., who was his pitching coach in 2023-24, called Weathers “Super competitive, probably an over-worker and a thinking man’s pitcher.” Stottlemyre said Weathers could be his “own worst enemy” because he wants to work so much — Stottlemyre cited his hunger to throw a lot between starts. But he added, “This is a guy who’s going to keep his nose clean, work his ass off, study, study, study. He’s smart. If he puts together a year where he can stay healthy and stay out there, you’re going to see a top-tier pitcher. You really are. It’s that kind of stuff. When he is out there on a regular basis, his stuff spells ace.” If Weathers is even close to that, it would be a change for the better from 2025 for the Yankees.

-

Mickey Lolich Mickey Lolich described himself as “the beer-drinker’s idol.” With his portly physique and likable disposition, the pitcher was popular with Tiger fans during his 13 seasons in their uniform. His talented left arm didn’t hurt his cause either. Of Yugoslav descent, Lolich was born in Portland, Oregon, September 12, 1940, the same day that Schoolboy Rowe defeated the Yankees to keep the Tigers a half-game ahead of the Indians in the American League pennant race. Lolich’s father was a parks director, which kept him outside, and his kids near the parks and play equipment. Consequently, Mickey (born Michael Stephen Lolich) developed into an outdoorsman and an athlete. Lolich said that as a kid he threw rocks at “birds, squirrels, and anything else that moved.” As a result, he built a strong arm. But Lolich was initially right-handed. As a toddler, he was favoring his right arm, until one day he tipped over a motorcycle onto himself. The bike landed on his left side, damaging his left arm and shoulder. That summer he wore a cast on his arm. When the cast came off he performed exercises to strengthen the torn muscles and Lolich became a southpaw. As a youth in Oregon, Lolich played lots of baseball, though there wasn’t a major league team to follow. “The only games we would get were national broadcasts of the Yankees,” Mickey said, “so I grew up idolizing Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford in the 1950s.” Later, Lolich and Ford would pitch against each other in the big leagues. Young Mickey served as visiting batboy for the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, where he met several baseball legends, including Lefty O’Doul. Lolich also met an umpire named Emmett Ashford, who later became the first African American umpire in the major leagues. As a teenager, Lolich pitched brilliantly for local Babe Ruth and American Legion teams, setting Oregon records for strikeouts that still stand. Lolich’s 1955 Babe Ruth team played in the Babe Ruth League World Series in Austin, Texas, in 1955 and his American Legion team was in the American Legion World Series in Billings, Montana, in 1957. One pitcher who Lolich battled in amateur tournaments was Al Downing,also a left-hander, who was later signed by the Yankees. In his first season in the minor leagues, playing under Johnny Pesky with Knoxville in the Sally League, Mickey weighed 160 pounds, and as he said, “was nothing but skin and bones.” Displaying an independent attitude that was his trademark, one year Lolich reported late to spring training because he took the civil service exam in Portland. With his eye on a job as a letter carrier should his arm ever fail him, Mickey was making sure he had a backup plan in place. During a stop in Triple A Denver he was struck by a line drive below his right eye. Lolich was gun-shy afterward, and his pitching suffered badly. Lolich’s refusal to take a demotion inadvertently led to him learning a pitching style that in turn led to his later success in the big leagues. After three seasons of bouncing on both sides of the Double A divide, Tigers General Manager Jim Campbell asked Lolich to report to the A-ball Knoxville Smokies again in 1962. Lolich, who didn’t like Smokies manager Frank Carswell, balked and instead flew home to Portland, telling the Tigers he was done. Shortly after, he toed the rubber for a semi-pro team, fanning 16 batters in relief and catching the attention of the Portland Beavers. Campbell arranged a deal to loan Lolich to Portland for the season. Pitching at home, the 21-year-old Lolich won 10 games and received pivotal advice from pitching coach Gerry Staley. A former big-league hurler, Staley advised Lolich to stop trying to fire the ball hard all the time, and to focus on throwing strikes. Lolich pitched brilliantly in spring training in 1963 but failed to make the Tigers’ roster. After a brief spell with Triple A Syracuse, Lolich was called up to Detroit in May, initially working out of the bullpen. Ironically, it may not have been his considerable fastball that enabled him to beat out other more highly touted lefties for the open spot on the roster. “That young Lolich is all business out there,” Detroit vice president Rick Ferrell observed. “I like his breaking stuff.” Staley’s advice had paid off. Lolich was evolving from a thrower into a pitcher. Lolich’s big-league debut came May 12, 1963, in a 9–3 Detroit loss to the Cleveland Indians. He struck out the first two batters he faced, Max Alvis and Sam McDowell. Later inserted into the rotation by manager Bob Scheffing, Mickey earned his first win May 28 in Los Angeles against the Angels, going the distance. Complete games became a Lolich trademark. Later in 1963, he pitched a one-hitter for eight innings against the Baltimore Orioles only to surrender a two-run homer with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, losing 2-1 to veteran Robin Roberts. “I guess you can’t beat an old pro,” Mickey said philosophically. In his first full season in the Detroit rotation in 1964, helped by a tip from new Tigers skipper Charlie Dressen (who had replaced Bob Scheffing in June of the previous season), Lolich won 18 games with a 3.26 ERA and 192 strikeouts in 44 games, 33 of them starts. As a scout with the Dodgers the previous season, Dressen had noticed that Lolich was tipping his pitches and helped the left-hander fix the flaw. In his windup, Lolich had been raising his arms higher when he threw his fastball and lower for breaking pitches. Mickey adopted a new windup and continued to show that he was more than just a fastball pitcher. “Lolich’s fastball is so good that he can get away with a mistake once in a while,” Dressen said. “But the big difference is that he comes in with the curve when he’s behind the hitter.” On April 24, 1964, Lolich fired a 5–0 shutout against the Twins in Minnesota, his first shutout in the big leagues. On September 9, he fulfilled a dream when he shut out the Yankees and his idol Whitey Ford, 4–0, at Tiger Stadium. American League batters began to take notice of the 23-year-old. “Lolich throws so easy,” Yankees slugger Mickey Mantle observed. “He keeps the ball down,” said Leon Wagner of the Cleveland Indians, “that’s why he’s so good.” Over a stretch in September, Mickey pitched 30.2 consecutive scoreless innings. The following year, Lolich’s 15 wins were surpassed by only three other AL lefties—Jim Kaat, McDowell, and Ford. His 226 whiffs ranked second in the league—the fist of four times he would be runner-up in that category (he led the league once). “I know I have some good years ahead in Detroit,” Lolich said after the 1965 campaign. “I don’t want to be an average pitcher. I want to be among the best.” On May 29, Lolich twirled a 10-inning complete game two-hitter to defeat the Indians 1–0 at Tiger Stadium. In 1966, Lolich struggled to get into a groove, battling inconsistency all season as he posted a 14–14 mark and saw his ERA inflate to 4.77. However, he did become the first Tigers pitcher since Hal Newhouser to win opening day starts in back-to-back seasons. By the end of the 1967 season, which saw Detroit battle for the pennant until the final day of the campaign, Lolich was establishing himself as one of the finer hurlers in the league. He finished the season with 28.2 scoreless innings. “That’s the best left-hander I’ve seen all year,” Boston slugger George Scott said after Mickey fanned 13 Red Sox batters late in the season at Tiger Stadium. Even curmudgeon Eddie Stanky, the White Sox manager who once tagged Lolich as a “second-line pitcher,” compared the southpaw to Hall of Famer Lefty Grove. A member of the Michigan Air National Guard, Lolich missed 15 days due to military service in 1967, seeing action during the riots in Detroit that served to fuel racial tensions in the city. After suffering a 10-game losing skid in the middle of the season—his 5.09 ERA during this stretch was one cause, but his teammates scored just 18 runs—Lolich roared through his last 11 starts, going 9–1 in the process. He threw 87.2 innings in those 11 starts, allowing only 50 hits and 18 walks while striking out 81 and posting a 1.33 ERA. Lolich credited pitching coach Johnny Sain, who became a good friend of his, with helping him become a complete major league pitcher. Sain’s laid-back approach and his reluctance to run his pitchers appealed to Mickey. Gradually filling out his frame, Lolich accumulated a noticeable belly, which some observers called flabby, but which he insisted, half-serious, was “all muscle.” Tigers manager Mayo Smith called him “my sway-backed left-hander.” “I do have a big tummy, I’ll admit,” Lolich once said. “There’s nothing I can do about it. It’s my posture. When I’m going good, nobody says anything about it. If I lose a few games they start saying I’m out of shape.” In 1968, the Tigers had the best team in the American League, coming from behind to win several games on the way to the pennant. Teammate Denny McLain won 31 games that year, overshadowing another fine season by Mickey (17–9, 3.19 ERA, 197 Ks), who actually had been pulled from the rotation in early August for poor performance. He had six appearances out of the pen before returning to the rotation. But after going 10–2 to close the season, Lolich took center stage in the World Series. The Tigers squared off against the St. Louis Cardinals, the defending world champions. After McLain lost Game 1 to Cardinal ace Bob Gibson, Lolich righted the ship by winning Game 2, 8–1 on a six-hitter. In that game, Lolich hit a home run off Nelson Briles in his first at-bat—amazing considering he was a career .110 hitter with no regular season home runs. “I wish I could pitch against hitters like me all the time,” Lolich once quipped about his lack of offensive prowess. In Game 5, with Detroit trailing three games to one in the Series, Lolich outdueled Briles again, winning 5–3 in his second complete game. Cardinals speedster Lou Brock admitted that Lolich was tough, saying it was hard to pick up the delivery until the ball was almost on top of the plate. Detroit won the next game in a rout to set up a seventh game match between Gibson and Lolich, both of whom had two wins in the fall classic. Detroit erupted for three runs in the seventh inning and Mickey went the distance to win, 4–1, on just two days’ rest. In the game, Lolich picked off two runners—Brock and Curt Flood—in the bottom of the sixth inning as he stymied the favored Redbirds. The southpaw had become the 12th pitcher to win three games in a World Series, and the last to win three complete-game Series contests in one year. “I didn’t know how long I could go,” Lolich recalled. “After the fifth inning, Mayo looked at me every inning and I would tell him I was okay. Then, when [they] got me some runs in the seventh, I told Mayo I would finish it.” As MVP of the World Series, Lolich earned a new sports car. “I hope it has a stick shift,” said Lolich, a car and motorcycle lover known for his fondness for going fast. In fact, during most of his career in Detroit, Lolich traveled the 33 miles from his suburban home to Tiger Stadium on his motorbike on the days he pitched. Another perk for the Series hero: Vice President Hubert Humphrey invited Mickey and Joyce Lolich to watch the liftoff of Apollo 8, the first mission to the moon. Lolich was already a space buff; he arranged annual tours of the space center at Cape Kennedy for Tigers players and their wives during spring training. His performance in the 1968 Series seemed to buoy Lolich. In 1969 he won 19 games and earned his first All-Star selection. His 271 strikeouts were the third-highest total in Detroit history, trailing only Denny McLain’s 280 in 1968 and Hal Newhouser’s 275 in 1946. Twice in ’69, Lolich fanned 16 batters in a game, his career high. In 1971 Lolich shattered that team mark for Ks as he racked up 25 victories and finished second in Cy Young Award voting to Vida Blue. His 308 strikeouts paced the league, he started 45 games and completed 29, and he logged an incredible 376 innings pitched. “I don’t like to hold back,” Lolich said of his stamina. “I have a God-given good arm.” Lolich credited part of his success in 1971 to the addition of the cut fastball, a pitch that Sain had been trying to teach him for years. Warming up one day in spring training, Lolich noticed his fastball dipping and moving in unusual ways and realized he had finally gotten what Sain had been preaching. Armed with his new pitch (which some batters mistakenly assumed was a slider because it moved down and away so much), from 1971 through 1974, Lolich reached the 300-inning mark every season. The lefty used an unusual method to keep his arm fresh in order to rack up all those innings. “I never used ice. I would stand in the shower after a game and soak my pitching arm under hot water for 30 minutes,” Mickey explained. “The water was scalding hot. After 30 minutes [my arm] would be red, but it would feel fine and I’d be throwing on the sidelines in two days. I never had a sore arm.” Lolich was nearly as effective in 1972, winning 22 games as he helped lead the Tigers back to the postseason. In his final start of the regular season, the lefty dominated the Red Sox at Tiger Stadium, fanning 15 batters to vault Detroit ahead of Boston by a half-game. As usual, Mickey was a workhorse, pitching 41 games, completing 23, and hurling more than 300 innings. He finished third in Cy Young voting behind Gaylord Perry and Wilbur Wood. In the playoffs against the A’s, Mickey pitched brilliantly, posting a 1.42 ERA in two starts, but he lost one game and got a no-decision in the other as the Tigers took Oakland to the limit before losing the decisive Game 5. Through most of his career, Lolich was a two-pitch pitcher. He threw his fastball in the low to mid-90s and relied on a curveball to set it up. In 1971, he added the cut fastball which he could throw in a few different ways to have it dip or move in or out. Regardless of what pitches he used, Mickey’s philosophy was simple: stay ahead of the hitters and let them get themselves out. “I tried to throw two of my first three pitches to a batter for strikes,” Lolich said. “I was like, ‘Here, hit it.’” But his fastball was hard to hit, and Lolich went on to fan more batters (2,679) than any other lefty in American League history, a record that still stood in 2007, more than three decades after he tossed his last pitch in the league. “I can’t throw as hard as Sam McDowell and a lot of guys,” Lolich said early in 1966. “Dave Wickersham showed me something two years ago. He doesn’t throw hard at all. [He’s] got control and he makes the hitter go after his pitch. That’s what I have to do.” Lolich captured 16 victories in both 1973 and 1974, and on May 25, 1975, he defeated the White Sox, 4–1, in a rain-shortened seven-inning game at Comiskey Park for his 200th career victory. But the season was one of frustration for the veteran left-hander. Mickey suffered one of the worst stretches of offensive support in baseball history in the second-half of 1975. While the Tigers were on their way to their most dismal season in more than two decades, Lolich pitched effectively but had little help. Over the course of 14 starts from July 11 through September 13, Mickey received a total of 14 runs from his offense! Not surprisingly, Lolich’s record was 1–13 during the stretch, which included a 19-game losing streak by the Tigers. When Mickey toed the rubber on July 11, he was 10–5 with a 3.31 ERA. When he lost the last of the 13 games during the 14-game stretch, his ERA was just 3.88, but his record had sagged to 11–18. He won his next start September 20—his teammates scored five runs for him—but it was his final game in a Detroit uniform. After the season, Lolich was dealt to the New York Mets for Rusty Staub in a trade that was unpopular with Tigers fans. Mickey never took to the Big Apple and never moved his family there. During his one season as a Met, he battled with the trainer and pitching coach, who wanted him to run and treat his arm with ice. Lolich balked at the advice. He managed a decent 3.22 ERA for the Mets, posting an 8–13 record in 1976. His biggest highlight in a Mets uniform came July 18, 1976, when he fired a two-hit shutout over the Braves at Shea Stadium in which he fanned four and did not walk a batter. At the end of the 1976 season, fed up with New York, Lolich retired in order to get out of the last year of his two-year contract. After sitting out a year, Mickey signed with the San Diego Padres, who pursued him and gave him a two-year deal. While playing with the Mets, Lolich had enjoyed visiting San Diego and felt it would be a wonderful place to finish his career. With a young Padres club he performed well in 1978 out of the bullpen, going 2–1 with a 1.56 ERA in 20 games. The following season, Lolich introduced a new weapon to his pitching arsenal: the knuckleball. After an inconsistent 1979 season, Lolich retired and returned to his home in Michigan. In 2003, Lolich was one of 26 players selected to the final ballot by the Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee. He received 13 votes, placing him far below the 75 percent required for election. Again in 2005 and 2007, Lolich was one of the few players to appear on the Hall’s Veterans ballot, but he fell far shy of enshrinement. Lolich won 217 games in his 16-year career, fanning 2,832 batters in 3,638 1/3 innings. He was named to the All-Star team three times, and earned the 1968 World Series Most Valuable Player Award for his historic performance and three victories over the Cardinals. He completed nearly 40 percent of his starts, and hurled 41 shutouts.

-

7 out of 10, 61 seconds. No matter how I look at it I had a bad day.

-

Mcoll, what I did for all my season mods on Windows 7 and 10 is I have a shortcut on my desktop and then I right click on properties and I look for where it says "run as administrator" and I click on that. That will save the option. The next time you run the game you right click on run as administrator and before you get into the game the system will ask you if it is ok to proceed. Try that out.

-

10 out of 10, 38 seconds. I'm in first place today because no one else has played yet!

-

6 out of 10, 42 seconds. I got that many right because they threw in two baseball questions that were more suitable for Fridays.

-

8 out of 10, 55 seconds. This was my best game since Sunday. The past two days have been tough. That has to be tough but you still manage to do very well here. Sometimes these questions are impossible and it doesn't matter what language you are most familiar with. I get that way on Tuesday and Thursday.

-

5 out of 10, 43 seconds. Second bad day in a row but this one's going to work against me. When you win a day getting only six right like I did yesterday then you know the questions were hard. Today's questions were typical Tuesday questions.

-

6 out of 10, 91 seconds. This one was a struggle today and I was astounded I got six right.

-

Thank you everyone. I have no room for error up against you guys.

-

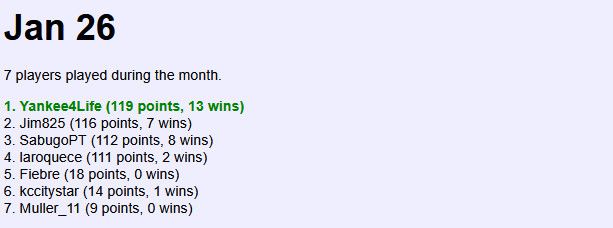

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Not a bad way to start the month but of course this is easy question day. Here are the results for January. It was nice to see that three other people played.

-

10 out of 10, 80 seconds. Slow and steady was what I was trying to accomplish today but not that slow. And I'm telling you Sabugo and Jim I am amazed at how you two can get under-thirty scores constantly.