-

Posts

26976 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

4 out of 10, 97 seconds. The great equalizer for me in this trivia game. General\Intermediate means General\You suck for me. 😄 Nascar doesn't exist for me because I can't stand it. I never pay attention to it.

-

Who knows Jim? So I looked it up here on Baseball reference. The Most Valuable Player Award is given annually to one player in each league. The award began in 1911 as the Chalmers Award, honoring the "most important and useful player to the club and to the league". This award was discontinued in 1914. From 1922 to 1928 in the American League and from 1924 to 1929 in the National League, an MVP award was given to "the baseball player who is of the greatest all-around service to his club". Prior winners were not eligible to win the MVP award again during this time. The current incarnation of the MVP award was established in 1931. The Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA) votes on the MVP award at the conclusion of each season before the postseason starts.

-

8 out of 10, 49 seconds. I did terrible and let me show you why. As a Yankee fan I hang my head in shame. My excuse is that I read it too fast and therefore messed up. I'm ashamed. For my penance I will say something nice about Rafael Devers. He had a good season in 2023. There, that's it. Done. December is arriving on Friday Jim believe it or not. This has been a fast month and with the extra day in December it is going to make the trivia race even more exciting.

-

Thank you. I enjoy doing it. Every player I feature I learn something about. Baseball history is wonderful to read about. I've had many months like that too Jim, kind of like I am stuck in place and no matter what I did I couldn't get going. Usually it is watching Fiebre pass me by. Those "general" questions are coming so I am not home free yet.

-

Thank you very much Marty.

-

Napoleon Lajoie was the first star of the newly formed American League back in 1901. He was so popular that when he went to Cleveland the team was renamed the Naps. Let’s see that happen today. I doubt if any team will rename themselves the Ohtanis if he happens to sign with them. 😅 Anyway, I doubt you will miss this question again after this.👍 Nap Lajoie. Career .339 average with 3, 252 hits. A really good player.

-

I hope you don't mind but I have to correct you. You have helped here on this site in more than "one tiny way" as you put it. You have maintained the transaction thread for such a long time that we almost overlook how effortless you seem to do it. You don't miss a transaction and you are always on top of things. If a player is released we can be sure to read about it immediately or if the latest the very next day. You do a fantastic job at this and I just want you to know this. Thank you for saying that. I think what he does around here is so important. You are referring to KGBaseball. He did make good rosters but I can not point to them in the download section because he, along with a group of other modders pulled their modws from this website and brought them over to EAmods, which is no longer around. His work was more than good enough to be featured here but that’s how it is. Others like UncleMo (audio) Spungo (Uniforms, etc) and a guy named piratesmvp04, who made two total conversion mods for Mvp 2004 do not have their work here either. Anyway, that’s that. However if you really want to see KG’s work just download the Mvp 2007 or 2008 mod because his rosters are there. That is the only remaining example of his work here and as far as I am concerned that is more than enough.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Now if the end of the month was tomorrow I'd be fine. I have done the same thing many times.

-

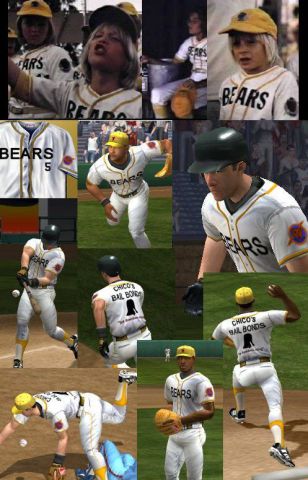

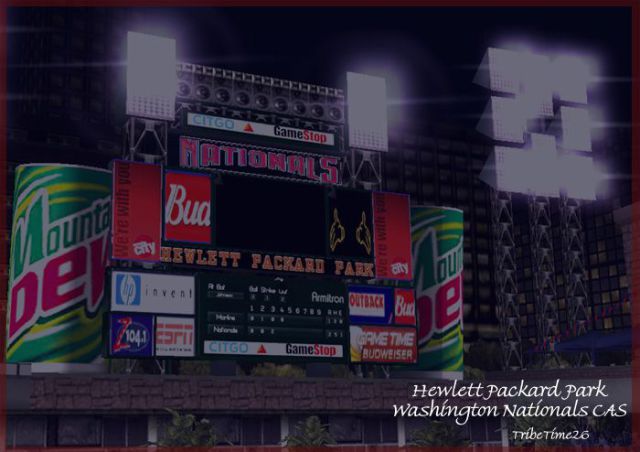

This week’s submission to the best of the best of the modders whose contributions to this website help make this website the number one baseball gaming site anywhere. One of the modders this week made uniforms for Mvp baseball 2004 and is a name only a few here now will recall. The other is a modder is someone who provided some minor fixes to the look of the game and once implemented made it look better. And our Behind the Scenes modder is someone who, while having some mods available for individual downloads, provided many portraits and cyberfaces for the Mvp 2006, ‘07 and ‘08 mods. IronForge It is unfortunate that IronForge did not continue to make uniforms when Mvp 2005 came out because he had a knack of making some very good ones just like the many other uniform makers that we have here. Maybe that was why he discontinued his mods but we’ll never know. His Bad News Bears uniform was a nice addition to my game and I recall placing it in one of the All-Star team uniform slots. His other uniforms such as his 1979 Oriole throwbacks were just as impressive. Keep in mind that you can use any of these mods in your Mvp 2005 game. Bad News Bears Uniforms (for Mvp 2004) Pirates Turn Ahead the Clock uniforms (for Mvp 2004) 1973 Pirates Throwback Away Uniforms (for Mvp 2004) 1979 Orioles Throwbacks (for Mvp 2004) Halofan Halofan was a dedicated and loyal Anaheim Angels fan. Notice that I said Anaheim. This caused a bit of controversy back when he was making his stadiums because some folks were commenting that he was pushing back too hard when Angels owner Arte Moreno renamed them to the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. He was having none of that and he made a stadium that showed how he felt. He had ads in the stadium that said savetheanaheimangels.com and the ad for the Los Angeles Times has been replaced with one for the Orange County Register. Also there are placements in the stands to show how he felt. All this plus a well-made stadium is a ball park worth checking out. I have always wondered how he felt when they officially changed the name to the Los Angeles Angels before the start of the 2016 season. Halofan’s Mvp 2005 Scoreboard fixes HaloFan’s “New” Icon Remover HaloFan’s Angel Stadium Of Anaheim - The Protest Edition: Day And Night Version Behind the Scenes Kriegz (better known as Tribetime26) Tribetime26 was a huge Cleveland Indians fan whose mods were mostly about the Indians be it his faces or portraits although he did branch out and do other teams too. His contributions were included in the very popular season mods from 2006 to 2008. He also made a fantasy Washington Nationals park not long after they left Montreal. TribeTime26s Chicago White Sox Portrait Pack v1.1 TribeTime26s Cleveland Indians Cyberface Set v1 TribeTime26s Tampa Bay Devil Rays Complete Photoset TribeTime26s Hewlett Packard Park (Washington Nationals CAS) v1.0 *I recommend you do not use any of the cyberfaces or portraits because they are just being posted here to show examples of his work. Putting these in your game will cause crashes. The ball park won’t.

-

9 out of 10, 49 seconds. I'm trying my best to come on strong but there's a lot of time for me to mess up.

-

10 out of 10, 39 seconds. I needed this a lot because I am running out of time this month.

-

8 out of 10, 72 seconds. A minor miracle today. I never do well in the General\Easier category.

-

9 out of 10, 55 seconds. A good comeback because I really needed it to keep up with you guys. You will not believe the one I missed. Laroquece was just talking about the Rockies in the shoutbox and here was the question.

-

Jack Bentley Many players in this thread you have heard of but it is my intention to have you walk away with some new information about every one of these players featured here. Today’s is about one of the first two-way players who played during Babe Ruth’s time and if his luck would have been a little bit better he would not be so obscure today. I always learn something about all of these players no matter how famous they were. The history of baseball is a fascinating and wonderful thing to discover. When the Los Angeles Angels signed Japanese superstar Shohei Ohtani, the baseball world has two-way players on the mind, yet the idea of the two-way player is far from a new one. Decades ago, it was not uncommon to find many a pitcher who handled the bat nearly as well as they performed on the mound. Few, however, truly excelled at both at the same time. One example from early in the 20th century was Jack Bentley. John Needles Bentley was born on March 8th, 1885, in a Quaker farming community in Sandy Spring, Maryland, to an affluent family. Living so close to the Washington Senators, Bentley was an ardent fan of the team. Indeed, the Senators would play an important role in his development as a professional. Soon after departing home for the George School in Newtown, Pennsylvania, a Quaker day school, Bentley became an accomplished pitcher. He would leave the George School at age eighteen, already a major-league prospect. It is reported that Bentley threw “several” no-hitters while in high school. Less than a year after becoming a student at the day school, Bentley was approached by Bert Conn, then manager of the Johnstown Johnnies in the Class B Tri-State League, a league which included teams in Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey. Conn offered him a contract to play the outfield at $75 a month, equivalent to slightly less than $1900 in current value, but the teenager turned him down. It was a pivotal time for Bentley. His father was enduring health problems that would eventually overcome him, and the farm had to be tended as well. This is where Julian Gartrell entered the picture. Gartrell, a doctor in the DC area, took notice of Bentley and mentioned him to his friend, Senators manager Clark Griffith. Bentley was playing for a county team by the time Dr. Gartrell found him, and after a particularly well-pitched game, the doctor suggested to Bentley that he go to Griffith Stadium to try out for the Senators. Bentley took that chance, and Griffith liked what he saw, though Bentley had no expectation that anything good would come of the tryout. Bentley was put on the mound by Griffith to pitch batting practice. Senators catcher John Henry, at the time, expected little to come of the eighteen year-old's performance. And yet, batter after batter looked baffled against the young lefty. After twenty minutes or so, Griffith had seen enough. He would offer Bentley a season-long contract for $600 ($100 per month). Bentley wouldn't accept it without first discussing it with his parents, who felt baseball wasn't a worthwhile vocation. The general atmosphere among professional ballplayers, where drinking, gambling, philandering, and generalized chicanery were commonplace, caused further hesitation in the minds of the Quaker family. After he gave his word that he would abstain from such activities, his parents gave their blessing. Bentley, amazingly, went straight to the majors, making his MLB debut on September 6th, 1913, against the New York Yankees. He entered the game in the ninth in relief of Joe Engel, with the score 9-1, Senators. He retired right fielder Frank Gilhooley on a fly ball to center fielder Clyde Milan, shortstop Rollie Zeider lined out to center as well, and catcher Ed Sweeney grounded out to second baseman Frank LaPorte. It was a low-pressure appearance for Bentley, but Griffith wanted to see what he could do without throwing him to the wolves just yet. Bentley made his first start for the Senators on October 1st against Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics. Again, he pitched brilliantly, allowing four hits in eight innings to get the shutout and his first win in the majors. Appearing in relief three days later vs. the Red Sox, Bentley tossed two shutout innings while allowing only one hit. By the time that Spring 1914 rolled around, Senators veteran Nick Altrock had taken a personal interest in Bentley's future. Bentley would spend the first two months with the big-league club, but despite posting a 5-7 record with a 2.37 ERA over 125 1/3 innings, Griffith still felt Bentley needed to spend a bit of time in the minors, sending him to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association on June 12th. This was after he was given a new, $1800 contract for the 1915 season. Much of Bentley's newly-developed difficulty on the mound had to do with the Senators attempting to change his delivery, making him pitch from the stretch exclusively. This caused him an unspecified arm injury, for which he sought treatment after his demotion to Minneapolis. Unfortunately, the man he saw to treat his arm was none other than “Bonesetter” Reese, who had gained a sort of notoriety for his (ahem) nuanced approach to the various ailments of the baseball player. It was, perhaps, this series of events, as much as anything else, that set him on the path on which he found himself for much of the next four years. While Bentley would continue on the mound for Minneapolis in 1916, Baltimore Orioles owner Jack Dunn would acquire his services a little more than halfway into the season as part of a rebuilt roster that would become the best Orioles team since the 19th century. Dunn was aware of the sort of offense that Bentley could provide; in 1915 with the Millers, Bentley was primarily a pitcher and still struggling with the aforementioned shoulder injury (7-4, 3.18), though he was a key member of the pitching staff. In 1916, Bentley's numbers on the mound were less than stellar (8-6, 4.15), but in 78 at-bats he batted .308 with six doubles and two triples. As 1917 began, the Orioles got off to a hot start in the International League, with Bentley splitting time between the outfield and first base, batting .343 over 93 games. He added 17 doubles, 11 triples and five homers, but this would be far from his best season. He would take a hiatus in 1918 to join the war effort in Europe, being assigned to Camp Meade and making sergeant seemingly overnight. Initially, Bentley was expected to remain at Camp Meade, where he would be a drill sergeant, but fate would have other plans. By June in that same year, Bentley had earned his commission. Now a second lieutenant, he would be deployed with the 313th Infantry, eventually commanding Company L, and would see action in the Argonne. He would be transferred to the 125th on Armistice Day. It was an experience that would remain with him for the rest of his life. Bentley would be cited twice for bravery during his time in the European Theatre, earning the Distinguished Service Medal. By the time his tour was ending, he was being considered for a promotion to captain. Bentley would say that after he returned from the battlefield, he no longer held such fascination for opposing players as he did before. He had talked about how it sometimes filled him with awe that he was playing with and against the very same players he used to idolize. Now, they all just seemed like Regular Joes, to him. After the experience of seeing hundreds of men in life-or-death situations, his perspective changed dramatically. Whether or not that played a role in his transformation from successful pitcher to top-tier hitter is debatable. The numbers speak for themselves: in 1919, Bentley would bat .324 with 24 doubles, 10 triples and 11 homers in only 92 games. The following season was even better, as he would bat .371 with 39 doubles, 12 triples and 20 homers. Bentley posted 231 hits in 145 games, that year. But as good as he was then, the next season was nearly legendary. Leading the International League with an astounding .412 average, he also led in homers, hits and doubles, as well as slugging percentage (.665) and total bases (397). What made these numbers all the more impressive was the face that he also made 18 appearances on the mound, going 12-1 with a 2.34 ERA. After the 1922 season, when Bentley batted .351 in 153 games and dropped his ERA to 1.73 while going 13-2 in 16 appearances on the mound, Dunn decided to strike when the iron was red-hot. By that time, Bentley was ready to retire if he couldn't get back to the majors; the International League could keep players virtually as long as they wished, as they were not part of organized farm systems at that time. New York Giants manager John McGraw was desperate for left-handed pitching at the time, and even though a 22-year-old Lefty Grove was a teammate of Bentley's, the $100,000 price tag for Grove was just a bit too steep for the Giants. Dunn would sell Bentley's contract to the Giants for $72,500. Had the Giants kept Bentley either in the outfield or at first base, it's possible that he could have been far more useful to the team. However, George Kelly had him blocked at first, and the corner outfield spots belonged to Ross Youngs and Irish Meusel, with Casey Stengel as the primary 4th outfielder, Bentley was signed specifically to pitch full-time. By this point, he had missed a great deal of developmental time on the hill switching from pitcher to outfield/first base, as well as time lost to the war, and he had never played a full season in the majors in any capacity. Going 13-8 with a 4.48 ERA in 31 appearances, at least his bat carried over to the big leagues with him, as he batted .427 in 94 plate appearances with nine extra-base hits. His pitching stats improved in 1924 as he finished 16-5 with a 3.78 ERA in 28 appearances. His hitting tailed off (.265 average, 0 home runs and six RBI), but it would pick back up in 1925 (.303 average, three home runs, eighteen RBI) as his pitching totals spiraled downward (11-9, 5.04 ERA). Aside from modest totals in 1926 (.258 average with the Giants and Phillies), Bentley would spend the remainder of his pro career with various minor-league teams, where he would alternate between the field and the mound, still batting very well. However, his time on the mound was a poor contribution by comparison. For his career Jack Bentley recorded a 138-90 record on the mound, with a 4.61 ERA. He had a lifetime average of .291 with 7 home runs and 71 runs batted in. His was not a common sort of career, but it was certainly not the only one in which a professional player found success on the mound and at the plate. It would have been very interesting to see how well he would have done had he been properly managed.

-

Ok, who in the hell is Yerry De Los Santos and why do we need him?

-

6 out of 10, 58 seconds. God was with me here because I only knew two of the ten questions. I guessed right on the other four. Running out of time here to catch up.

-

6 out of 10, 91 seconds. These were really tough today and I was very fortunate to get six right.

-

Random Thoughts On A Sunday Morning Updated To 11-24

Yankee4Life replied to Yankee4Life's topic in Left Field (Off-Topic)

Updated to 11-19 ...I haven’t spent any time thinking about who the Yankees are going after in free agency or who they might get in a trade because I’ll be honest with you guys I don’t care anymore. The way I see it they are an embarrassment on and off the field with Brian Cashman bringing down the team recently with his recent comments about the team itself when he said that they were “pretty f–king good.” That comment alone should have had him fitted for a straight jacket. Also his comments about Giancarlo Stanton, while being 100% true, was not something a team executive would or should say about a player currently on the roster. Sure Stanton is going to get hurt next year and probably sometime during the first ten games but to publicly show him up is not the way to go about doing things. ...The World Series last month between Texas and Arizona did not get good ratings despite it being an exciting and well-played one. That’s too bad because people missed out on a good series between two teams who deserved to be in there. Just because a series that does not have the big east coast cities or Los Angeles or Chicago does not mean that it’s to worth watching. I may not like all the rule changes this sport has made over the past couple of years but it doesn’t mean that I don’t want them to succeed. Selfishly I would have liked to have seen the Yankees in it but that won’t be happening for a few years now because they have more problems then you can shake a stick at but these two teams showed that you don’t have to come from a major market to put on a good World Series. Now only baseball needs to do is to figure out a way to make people tune in to find out. ...I was watching parts of the N.L.C.S. between Arizona and Philadelphia and I had to laugh at Phillies outfielder Brandon Marsh. This guy looks like he hasn’t washed his hair since spring training and as far as shaving it looks like it’s been a few years for him. But I had to laugh because if the Yankees got him in a trade (he is a left-handed hitter and that is what they need) he would be looking at least a ninety-minute haircut and shave due to the length of the hair and beard and the possibility of not knowing what they’d find in there. ...The average time of a nine-inning game decreased from three hours and four minutes to two hours and forty minutes during the 2023 season. Yeah, well ok. But I can recall when a baseball game was completed in shorter times and that included things like unlimited throwing to first base and catcher visits to the mound. Games will not get shorter until they tell people like FOX that they are not the reason why people tune in and that they should take a back seat to what’s going on. ...In a very unfortunate situation an Ivy League student with a heart condition died after she drank Panera Bread’s Charged Lemonade, a large cup of which contains more caffeine than cans of Red Bull and Monster energy drinks combined, according to the lawsuit filed by her grieving parents. The twenty-one-year-old student had a heart condition called long QT syndrome type 1 and avoided energy drinks at the recommendation of her doctors so it is unclear as to why she drank this Charged Lemonade when there is a notice in front of the different flavors of this drink that informed her and everyone else about how much caffeine was in the drink. What I am wondering is if she was told by her doctors to avoid energy drinks, then why did she order one? I'm sad for her and her family but Panera isn't at fault here and it is clear to me at least that the parents are trying to get something out of Panera in the way of a settlement because they don’t want this to go to trial due to the fact that they will probably lose. I think it boils down to this. At one point, even Ivy League college students who are supposed to know everything need to figure out how to be responsible and understand what we're consuming. When you see a drink that is “charged” it should tell you that it is no ordinary drink and when the signs informed the patrons that the caffeine included in said drink was very strong should've been enough for this girl to avoid it, but she didn’t. She made as much sense as someone ordering a hot coffee from a drive-thru and acting surprised when their leg is burned if they accidentally spill it on themselves while driving. ...That answers that, Dept: Megan Rapinoe went down in the sixth minute with an injury she suffered in the final match of her career last week. The injury, a possible Achilles injury prevented her from returning to the match and after the game she replied that because she got hurt that there was no existence of God because as she explained that if there was a God, this (meaning her injury) was proof that there wasn’t. Well, that’s that. The question asked for thousands of years has been answered by probably the most selfish and disliked female soccer player ever and with her getting hurt I think that it proved that God may not have been that impressed with her behavior because as my mother always used to say to me when I did something wrong "The Lord punished you" and if anyone in women's soccer deserves punishment it is Megan Rapinoe with the way she conducted herself here and her insulting comments about our country. Her future may lie in providing commentary to women's soccer from now on but since no one watches we don’t have to worry about seeing her again. ...A Florida man (where else?) was arrested after bashed a woman's head into a tree stump because she woke him up on her way to the bathroom. And I bet some of you were thinking he had to have a reason. The couple were at the Silver Springs State Park campsite which is located in Northern Florida. The two people had been drinking before they retired to their marital sleeping bag and everything was just fine until the woman felt nature calling her and when she got up to take care of her concerns she tripped and fell over her big lug of a husband because it’s hard to find where to go when it is pitch black outside and you don’t have the luxury of turning on a light. So, proving the old adage that alcohol and logs do not go well together her husband got up and hit her with the log whereas if they were home and she did this to him he’d of just thrown the alarm clock at her. ...I found this out recently even though it happened a few months ago. The Colosseum in Rome may be over two thousand years old but it didn’t stand a chance between three idiots ranging from twenty-seven years of age to seventeen as they used the building to carve their names in. The first guy who did it, a twenty-seven year-old British man explained after he was caught via his lawyer that he did not know the “antiquity of the monument” when he was busy carving his name in it. At the same time I am sure he does not know the antiquity of Buckingham Palace or what that means to every British citizen. Not to be outdone a a seventeen-year-old girl from Switzerland was spotted carving her initials into a wall of the building by a tourist guide and the very next day, a seventeen-year-old student from Germany did the same thing although not in the same area. For the act on the Colosseum both teenagers risk a fine of up to $16,850 and up to five years in jail. If any of these three people are interested in becoming U.S. citizens one day they are well on their way to doing so and based on their behavior they will not have any trouble passing the test. ...I've been taking a break from social media because my heart breaks to see all of the horror, hate, and terror that's going on in the world. People being tortured and killed or any act of hate towards any one group is horrific. We need to protect ALL people, especially children and stop the violence for good. I’m sorry if my words will never be enough for everyone or a hashtag. I just can’t stand by innocent people getting hurt. That’s what makes me sick. I wish I could change the world. But a post won’t. -Selena Gomez Selena Gomez said these words not long after the start of the Isreali - Gaza war and for some reason people are giving her a hard time for it. Before I wrote this out to be included in here I read it over a few times and I can not figure out what she said to make people so upset with her. I still can’t. Besides that the world is full of people that are just looking for something to be upset about is still not a good enough reason come down on someone who doesn’t want people on both sides of this war to be hurt because this is all she has done here. The only thing I can think of is that she didn’t say what fans want to hear, so she got criticized. If a celebrity doesn’t take a side they also tend to get criticized and if they don’t say anything at all the same thing happens. Fans were complaining that they wanted her to take a position but her position is the very voice of reason the whole conflict is missing. ...Why do kids run around Walmart like it is one giant playground? ...Ever since the night that Will Smith walked up the stage and slapped Chris Rock I stopped being a fan of his and I even went as far as not watching any of his movies or reruns of The Fresh Prince of Bel Air. He’ll be paying for what he did for the rest of his life because I believe some people in Hollywood will never forgive him. I haven’t thought about him that much since that happened but this week I have because his wife Jada Pinkett Smith (or whatever she is) is coming out with her memoir entitled “Worthy” and from, what I have read about it so far she is anything but worthy. In it she writes that Tupac Shakur was her “soulmate. ” This was unnecessary and for no other purpose except to degrade her husband. She also went on to say that she and Smith have been separated since 2016 despite appearing as husband and wife in public. I tried to put myself in Will Smith’s shoes for a minute and I did not like it one bit. I am beginning to see what he did to Rock that night was a way to seek approval from a woman that had no intention of giving it. He deserves a better life than this because his entire legacy has been tarnished in less than two years thanks to her. Distancing himself from this woman will get his self respect back and he will find that Hollywood can be forgiving. Other actors have made huge comebacks after some far worse behavior. Robert Downey, Jr comes to mind. If Will Smith eventually does distance himself from her she is going to find that no one is going to want to be associated with her any more as soon as book sales and the talk show circuits wind down. ...If you look hard enough to be offended by something you are guaranteed to find it. I have always said this in the day and age of people on twitter giving their opinion on anything and everything. These are the same people that before twitter came about no one cared what they had to say but now that they have found a voice they are making up for lost time. The latest insulting and God-wrenching problem is from a fifty-year-old Thanksgiving cartoon special called A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving. In it, to sum it up in as few words as possible, Charlie Brown’s friends kind of invite themselves over for the holiday and he isn’t prepared to have anyone over since he is going to his grandmother’s house. But they come anyway and he makes them feel as comfortable he could. Complaints were made that there wasn’t any turkey or stuffing and in substitution Charlie Brown served up toast, jelly beans and popcorn. The problem is for the twitter people is the scene where they are having their “dinner.” (See screenshot.) One of the kids, a black child named Franklin is sitting alone on one side of the table and the others are on the other side. The issue -if you want to call it that- is that the black child is being kept separate from the rest of the kids and is being racially profiled. One could say that kid has the best seat at the table. I mean look at all the elbow room he has there! And this my friends is what some people spend their time doing online. What really bothers me is that I am continuously surprised by this. I remember when we were in school we talked about this cartoon the next day and we all thought it was funny because they had popcorn for Thanksgiving. The people that come up with these things deserve scorn and ridicule instead of being taken seriously. ...Finally I want to wish all of you located in the States a very happy Thanksgiving. For the rest of you it will be a typical Thursday without all the fuss but if you want to join in and cook a turkey go right ahead. As usual we have three NFL games on again along with one game being aired the day after. The Packers go to Detroit to take on the Lions at 12:30 p.m. on FOX followed by the Redskins visiting Dallas at 4:30 p.m. on CBS. I’ve grown to look forward to the Cowboys playing in the second game year after year because I can always put that game on and fall asleep. At 8:20 p.m. the 49ers travel to Seattle to play the Seahawks. That one will be on NBC. I won’t be watching that game at all. On Friday the 24th the Miami Dolphins will be playing the Jets in New York and that one starts at 3:00 p.m. You need to have Amazon Prime to see that one. I’m sure the NFL would even schedule a game for Saturday but they don’t want to get the college teams upset. So even if you watch one game or all four or none at all I want to wish you and your family a very happy and safe Thanksgiving. -

10 out of 10, 35 seconds. I needed this because there are less than two weeks left.

-

4 out of 10, 66 seconds. I don't know about anyone else today but these questions were extremely hard.

-

Mistaken on both parts I am sorry to say. I was 9 out of 10 in 44 seconds and I also noticed that they were not as easy today just like you guys did. However considering how I did yesterday I will be happy to take it.

-

You got that right. It is hard making any kind of distance from you and if I keep playing like I have been it won't matter.

-

Just like I predicted with Jim and laroquece. Good job you two.

-

MVP Baseball 2005 (The 2005 Season Mod)

Yankee4Life reviewed Muller_11's file in Total Conversion Mods

-

MVP Baseball 2005 (The 2005 Season Mod)

Yankee4Life commented on Muller_11's file in Total Conversion Mods

Thank you very much. You did a great job. Take your time doing future updates because I am sure this takes up a lot of modding time. Thank you again and let me know if you need anything else. When you are done with your updates for this I will review it. So far it looks great and you did a great job with this.