-

Posts

21580 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

10 out of 10, 37 seconds. It helped that I had two Ozzie Smith questions in a row.

-

7 out of 10, 45 seconds. It could have been a lot worse. I feel the same way!

-

Here is why I know who Faith Hill is. Other than that I would have said the same thing. She is a country-western singer and to this day I have not listened to one song she has. But she looks nice singin' them.

-

Jim, that is the all time record in here. You broke my record by one second!! I will be crying for the rest of the day! 😄

-

10 out of 10, 36 seconds. It's Friday. Enough said!

-

3 out of 10, 151 seconds. As usual, a terrible job on Thursday.

-

10 out of 10, 97 seconds. Big improvement over the past couple of days.

-

3 out of 10, 117 seconds. For me this is a good score on a Tuesday.😬

-

6 out of 10, 90 seconds. I missed a couple of trick questions that I honestly should have known. That is what happens when you try to go too fast.

-

10 out of 10, 38 seconds. These must have been leftover Friday questions because they were very easy.

-

4 out of 10, 109 seconds. These questions killed me today. Usually I can make good guesses but not today. It seems women are like that all over. You could be watching a game and they'll keep on talking about anything but what is going on and when a commercial gets on they are quiet. Go figure. 🙂

-

Try out this Logitech gamepad. It is cheap and it does the job and you can play Mvp again.

-

10 out of 10, 40 seconds. After the past few days I needed this. But then again it's Friday and we all know what that means.

-

2 out of 10, 189 seconds. Where did you go to college, figure skating and who played for what team in soccer all equalled today's high score. 😟

-

6 out of 10, 83 seconds. Jim, I was even luckier. Thankfully I had two questions concerning the Polo Grounds that bailed me out.

-

3 out of 10, 167 seconds. Ok, I will just move on and look forward to tomorrow. 😟

-

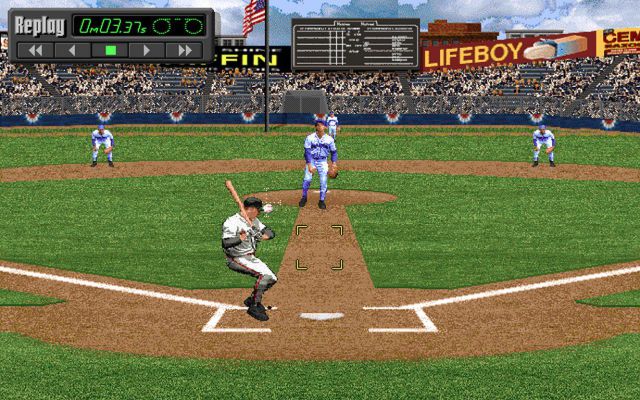

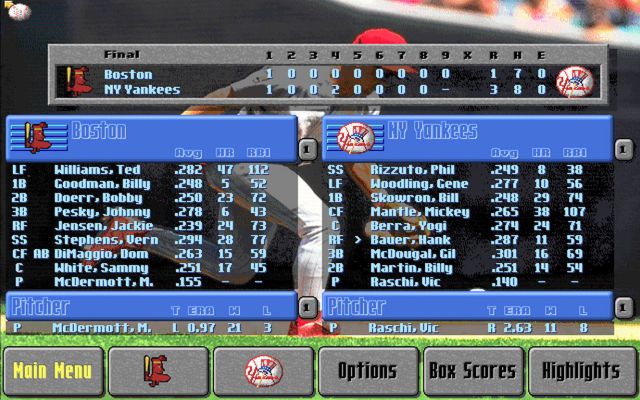

Another game. I still can't hit. Those fastballs from the CPU are unhittable. A nice double play to end the first inning. Vern Stephens triples down the right field line in the fifth inning with none out. He did not score. My obligatory hit batter occurred in the eighth inning when Dom Dimaggio was hit. If you look close where the ball is you can see the crosshairs that helps you locate the pitches. This is very helpful in this game when you want to knock someone down. Yankees win 3 - 1. Still not a good game because I once again struck out too much. Either I was swinging too early or too late.

-

9 out of 10, 58 seconds. As usual I missed the "gimme" question.

-

10 out of 10, 36 seconds. Wow, these were like Friday questions today. Here are the results for the month of August. It was a close one again.

-

8 out of 10, 70 seconds. Two questions tripped me up and it showed on my time.

-

10 out of 10, 35 seconds. It's Friday. Everyone is going to kill it today. I'm pulling for you all.

-

6 out of 10, 136 seconds. Typical Thursday!

-

6 out of 10, 80 seconds. I stumbled through these today. They were tough.

-

That's my signature move Jim.

-

8 out of 10, 75 seconds. This is what happens when I amazingly avoid soccer, rugby and NASCAR questions.