-

Posts

21580 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

AND YOU ARE ASKING THIS IN THIS THREAD?????? 😡😡😡

-

10 out of 10, 36 seconds. Even this good score is not god enough.

-

8 out of 10, 73 seconds. Big deal! Too little, too late. Hey, that's fine. Don't forget about two months ago I got a zero out of ten score. It was on a day we had those general intermediate questions.

-

10 out of 10, 46 seconds. Oh my God.

-

Congratulations Jim. You just won your first month!

-

5 out of 10, 56 seconds. World Cup questions, where did he go to college and something called the Brownlow Medal. And yet I got five right.

-

10 out of 10, 59 seconds. Oh did I get lucky!

-

5 out of 10, 75 seconds. And that will be that.

-

8 out of 10, 59 seconds. A good day tackling some tough questions.

-

10 out of 10, 37 seconds. Not bad today but probably not good enough.

-

7 out of 10, 67 seconds. That's ok. the ones I missed I honestly did not know.

-

10 out of 10, 33 seconds. I'm just trying to stay even with Jim because that guy owns Fridays.

-

6 out of 10,, 55 seconds. NCAA football, NASCAR (a sport I truly hate) and something called Euro 2004. Yet I got six right.

-

-

-

4 out of 10, ,63 seconds. These questions were too much today.

-

I echo what Jim said. Great score for this category. Welcome!

-

Start playing again every day because we need you and is more fun when you play along with us. And those rugby and cricket ones along with the World Cup and where somebody went to college ones are next to impossible for me.

-

I might. But if this was one week ago I'd feel more confident.

-

Jim it would be a minor miracle if I catch you with your seven point lead. The way I see it we have at least three general question days left and I have no clue on those days.

-

7 out of 10, 80 seconds. For some reason they asked me four baseball questions and I got them all right. That's the only reason why I got seven correct.

-

You have no problem with them!

-

7 out of 10, 73 seconds. I even got a question from the 1800's right today. Wow.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. A good day but I am not making up any ground. Jim's on a mission and he has an eight point lead. I looked at the calendar and besides the obvious fact that we have exactly two more weeks to go this month ends on a Sunday and that's going to help out Jim immensely because we have easy baseball questions on Friday, difficult ones on Saturday and then it's back to easy on Sunday and with the way everyone gets high scores on those easy days that will help Jim. Unfortunately I have two more weeks of the general questions to deal with and that holds me back.

-

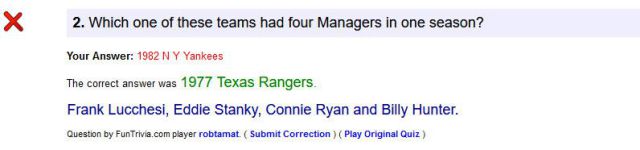

6 out of 10, 64 seconds. Not a good day at all. Checking the ones I got wrong I should have had one of them right. It was this one here. The reason why I said this was because in spring training that year a guy named Lenny Randle beat up Texas manager Frank Lucchesi because Bump Wills (Maury Wills' son) won the starting second base job. He was hurt so bad that I believe he had to be hospitalized.