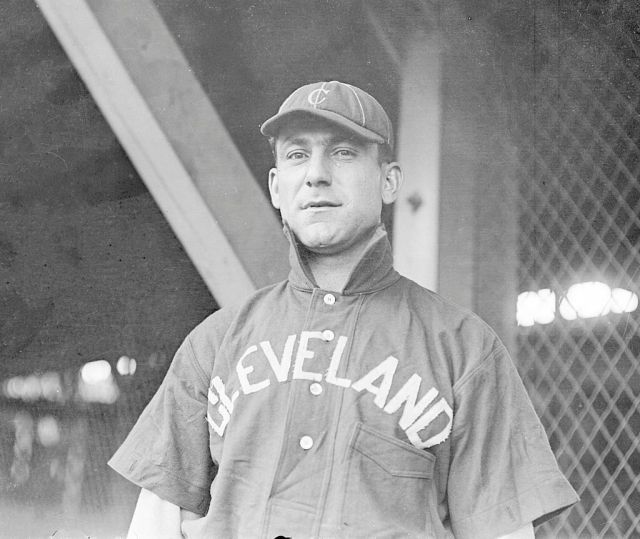

Roger Peckinpaugh

Roger Peckinpaugh was one of the finest defensive shortstops and on-field leaders of the Deadball Era. Like Honus Wagner, the 5’10”, 165-lb. “Peck” was rangy and bowlegged, with a big barrel chest, broad shoulders, large hands, and the best throwing arm of his generation. From 1916 to 1924, Peckinpaugh led American League shortstops in assists and double plays five times each. As Shirley Povich later reflected, “the spectacle of Peckinpaugh, slinging himself after ground balls, throwing from out of position and nailing his man by half a step was an American League commonplace.” The even-tempered Peckinpaugh was equally admired for his leadership, becoming the youngest manager in baseball history when he briefly took the reins of the New York Yankees in 1914. Described as the “calmest man in baseball,” Peckinpaugh’s steadying influence later helped the Washington Senators to their only world championship, and won him the 1925 Most Valuable Player Award, making him the first shortstop in baseball history to receive the honor.

From an early age, Roger took an interest in baseball, and probably received special instruction from his father, who had been a semipro ball player. When Roger was a boy his family moved to the east side of Cleveland, taking up residence in the same neighborhood as Napoleon Lajoie, the manager and biggest star of the Cleveland Naps. Roger grew up idolizing Lajoie, and matured into a fine all-around athlete, starring in football, basketball, and baseball at East High School. Lajoie noticed Peckinpaugh’s talent, and upon the youngster’s graduation from high school in 1909, offered him a $125 per month contract to play pro ball. Roger’s father was against his turning pro, so he asked his high school principal, Benjamin Rannels, for advice. Probably aware of Roger’s love for baseball, Rannels urged Peck to sign the contract, advising him to allow himself three years to make it to the majors. If he didn’t make it, then he should go to college. Peck was a regular in two years.

In 1910 the Naps sent Peckinpaugh to the New Haven Prairie Hens of the Connecticut State League for some seasoning before calling him up to the big league club in September. Peckinpaugh hit only .200 over 15 games in his first major league trial, and was farmed out the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers for the entire 1911 season. Peck made the big club to stay in 1912, but the right hander only hit .212 in 70 games. Based on that poor showing, the Naps gave the starting shortstop job to another youngster, Ray Chapman, and in May 1913 traded Peck to the New York Yankees for Bill Stumpf and Jack Lelivelt. Yankees manager Frank Chance installed Peck at shortstop, where he would stay for the next eight and a half years.

Given a chance to play regularly, Peck hit a respectable .268 in 1913, as the Yankees finished seventh. In 1914, Peckinpaugh’s average dipped to .223, though he played all 157 games, swiped a career-high 38 bases, and displayed the strong arm and superior range that would soon win him plaudits as one of the league’s finest defensive shortstops. Though he was only 23 years old, Peckinpaugh also emerged as one of the steadying influences in a distracted clubhouse. “The Yankees were a joy club,” Roger later remembered. “Lots of joy and lots of losing. Nobody thought we could win and most of the time we didn’t. But it didn’t seem to bother the boys too much. They would start singing songs in the infield right in the middle of the game.” In recognition of his leadership abilities, Chance named Peckinpaugh captain of the team, and the young shortstop soon won the confidence of all the players. When Chance resigned with three weeks left in the season, the Yankees made Peck the manager for the rest of the season. He still holds the record as the youngest manager in major league history.

Jacob Ruppert and Cap Huston bought the New York franchise after the 1914 season and started turning the Yankees into winners. Ruppert hired Wild Bill Donovan to take the managerial reins but he kept Peck as captain. With the Federal League dangling big money in front of established stars, the Yankees signed Peck to a three-year contract at $6,000 per year for 1915 to 1917. While he continued to post pedestrian batting averages over that span–topping out at .260 with 63 runs scored in the final year of his contract–Peckinpaugh repaid the Yankees’ loyalty with his glove, leading the league in assists in 1916 and double plays the following year. To aid his fielding, Peck liked to chew Star plug tobacco, and then rub the juice into his glove. “[It] was licorice-flavored and it made my glove sticky,” he later said. He also used the tobacco to darken the ball, “and the pitchers liked that. The batters did not, but, what the hell, there was only one umpire.”

According to Tris Speaker, opponents were able to cut down on Peckinpaugh’s batting average by cheating to the left side, where the right-handed dead pull hitter found the vast majority of his base hits. “Peck usually hits a solid rap when he does connect with the ball,” Speaker explained to Baseball Magazine in 1918. “But he has the known tendency to hit toward left field. Consequently at least four men are laying for that tendency of his….A straightaway hitter whose tendency was unknown might hit safely to left field where the very same rap by Peckinpaugh would be easily caught.” But after hitting just .231 in 1918, Peck began hitting the ball with more power, posting a career-high .305 average in 1919 with seven home runs. He followed up that performance with back-to-back eight-homer seasons in the lively ball seasons of 1920 and 1921, drawing a career-high 84 walks in the latter season. As further evidence of his expanding offensive versatility, Peckinpaugh also laid down 33 sacrifices, fifth best in the league. Two years later, he would lead the league with 40 sacrifices, and would eventually finish his career with 314 sacrifices, eighth most in baseball history.

In his first World Series in 1921, Peckinpaugh played poorly in the Yankees’ eight game loss to the New York Giants, as he batted just .194 and his crucial error in the final game allowed the Giants to win 1-0 on an unearned run. In the off-season Babe Ruth complained about the managerial skills of Miller Huggins (not for the first or last time) and said the Yanks would be better off if Peck managed them. Probably to avoid more conflict, New York traded Peck and several teammates to the Red Sox for a package that included shortstop Everett Scott and pitcher Joe Bush. However, three weeks later, Senators owner Clark Griffith, sensing that his team was one shortstop away from contention, managed to engineer a three corner trade in which the Red Sox received Joe Dugan and Frank O’Rourke, Connie Mack‘s Athletics received three players and $50,000 cash, and the Senators received Peckinpaugh.

The veteran shortstop teamed with the young second baseman Bucky Harris to form one of the best double play combinations in the American League. Everything fell into place by the 1924 season when owner Griffith appointed Harris the manager. Harris considered Peck his assistant manager, and together they led the Senators to back-to-back pennants in 1924 and 1925. Peck was the hero of the 1924 World Series, .417 and slugging .583, including a game-winning, walk-off double in Game Two. However, while running to second base (unnecessarily) on that hit, Peckinpaugh strained a muscle in his left thigh, which sidelined him for most of Game Three and all of Games Four and Five. But in what Shirley Povich called “the gamest exhibition I ever saw on a baseball field,” Peckinpaugh took the field for Game Six with his leg heavily bandaged and went 2-for-2 with a walk before re-aggravating the injury making a brilliant, game-saving defensive play in the ninth inning. Although Peckinpaugh had to sit out Game Seven, he had already done more than his share to bring the Senators their first world championship.

Peckinpaugh came back strong in 1925 and had a fine season. He batted .294 (approximately the league average) as the Senators won their second straight pennant. In a testament to his fielding and leadership abilities, the sportswriters voted Peck the American League MVP in a narrow vote over future Hall of Famers Al Simmons, Joe Sewell, Harry Heilmann, and others. Despite his strong performance, Peck’s legs continued to give him trouble, and by the start of the World Series they needed to be heavily bandaged. After carrying the Senators in the 1924 World Series, Peckinpaugh sabotaged them in 1925, turning in one of the worst performances in Series history. He committed eight errors, a Series record that still stands, although Peckinpaugh later groused that “some of them were stinko calls by the scorer.” Three of Peck’s errors led directly to two Senators losses, including an eighth-inning miscue in Game Seven that allowed the Pirates to come from behind to capture the championship. Peckinpaugh’s two errors that day, however, were perhaps understandable, as the playing conditions were so wet that gasoline had to be burned on the infield to dry it off. Still, it was the second time (after 1921) that a World Series had been lost due to a Peckinpaugh error in the deciding game.

Peck’s legs were giving out, and he would only play two more years in the big leagues. After retiring from the game following the 1927 season, Peckinpaugh accepted the managerial post for the Cleveland Indians. In five and a half seasons with Cleveland, Roger guided the club to one seventh place finish, one third place finish and three consecutive fourth place finishes before being fired midway into the 1933 season. After stints managing Kansas City and New Orleans in the minor leagues, Peck returned to skipper the Indians again in 1941, finishing in fifth place before moving into the Cleveland front office, where he remained until he retired from organized baseball after the 1946 season.

Peckinpaugh retired with a .259 lifetime average, had 48 home runs and 740 runs batted in. His managerial record was 500 - 491.